A holiday, a new book, and never let ’em know what you’re thinking. A post about New England homes, taste, class, and how John Adams enjoyed writing.

Ethics

Back in the early 2000s, I worked as the Creative Marketing Director for a cluster of radio stations in southern New York. In that capacity, I created and managed the stations’ websites, created graphics for events, created logos for the stations, and handled a myriad of other technical responsibilities. If someone needed to get it done, they’d ask me to do it. I’d take care of it. I was a one man band. I devised aspects of presentation and technology the others in the building never knew they wanted or needed until I gave it to them. I had fun at that job. I liked it a lot. It was the autonomy of it all – while I’m sitting at a computer, I much prefer to work alone. I’m not the type of person who needs a lot of input from others.

While I enjoyed having the title of Creative Marketing Director, I’m not certain of whom I was directing. Perhaps I was directing the work. After all, while I was included within the confines of a three person department, I was the only one who worked on certain projects. My two coworkers had responsibilities of their own, along with their own titles; Director of NTR (Non-Traditional Revenue) and the Assistant to the aforementioned position.

The reason I bring up this part of my life is because I’d like to mention a lesson I learned while employed in radio. Even though I had little or nothing to do with the actual airwaves, I spent a fair amount of time with those who did. And on one particular occasion, I learned a lesson I’ll never forget. One, at the time, I thought somewhat unscrupulous and even bordering on unethical.

We’ve all heard radio morning shows. On the more popular stations, they usually consist of a man and a woman who call themselves something like, “Rick & Mindy in the Morning,” or “Drive with John & Miranda.” As you may imagine, the two person team is very close and as you may also imagine, the team has the potential to become tightly woven into the fabric of a listener’s day. After all, if you drive to work at the same time each day of the week and listen to your favorite morning show every time you do so, you might become attached to those who comprise the show. If one person were to suddenly disappear or be replaced by someone else, well, let’s just say the experience might be somewhat jarring. It’d be akin to waking up in bed one morning next to a complete stranger. While the stranger may be the most amiable person you’ve ever laid eyes on, I’m sure you’d much prefer to lay your eyes upon them somewhere else. Or, at the very least, have them introduced to you before having them jump in your bed.

“He’s leaving. He’s decided to move back to his hometown in Iowa.”

“What? How can he just get up and leave like that? How are you going to break it to the listeners? He’s the most popular morning show host north of New York City. I’m assuming you have a transition plan.”

“Yes, our transition plan is to find a new host and on Monday morning, the new host will be sitting in the studio. We won’t even mention the change.”

“Just like that? Out with the old and in with the new? No mention of a new morning show host on the airwaves?”

“Nope. We never tell anyone anything. We just make the switch and people get used to it.”

To be honest, I thought this entire experience was incredible. I was befuddled after having that conversation with the Station Director. As of that moment, I hadn’t experienced an on-air employee transition like the one I described above and I wasn’t aware of how things were done. I thought we’d have some sort of radio going away party, where the jock who’s leaving would say his goodbyes and the incoming one would say his hellos. I actually thought about the situation for a while afterward and thought about how the listeners would react. I came to the conclusion that the Station Director was doing the right thing. There are some cases when giving a person too much information, or information that isn’t critical to their position, can actually do damage. In the case of the listeners, if they had been warned of their favored jock’s disappearance, the station would only incite drama. There would be complaints and phone calls and threats of switching to new stations. If the situation were handled similarly to ripping off a Band-Aid, there’d be a kerfuffle for a day or two and then the world would settle down as it was before the change. People would, as the Station Manager indicated, get used to it.

When blogging, or writing, or producing any type of content for that matter, the worst thing you can do is apologize. Or explain what’s going on behind the scenes. I’ve seen YouTube channels where the host stopped making videos for a time and upon his return, say something like, “Sorry for being away for so long. I’ve had some personal issues in my life. I’m really committed now though and I’m going to be posting regularly.” And then, of course, he falls off the face of the earth, never to be seen or heard from again. The same is true when it comes to blogging. Explaining to an audience that you’ve been gone is almost always a bad idea. They know you’ve been gone. And if they don’t, you just told them. A much better idea is to either stay committed in the first place or simply write or produce when you can. No need to inject a negative notion (your disappearance) into a reader’s or watcher’s mind. It’s sort of like radio – just do it. Write, produce, and hire a new jock for Monday morning. It’s not unethical to avoid certain types of negativity.

Why bring any of this up at all? I guess I was thinking about blogging and content creation as a whole. That’s what they call what we do in the internet world – content creation. I don’t think that’s what I’m doing here though. Personally, I simply enjoy writing and sharing tidbits about my life and about the area in which I live. I guess it’s a hobby. I’ve been enthralled with discovering things lately that I’ve oddly never even thought about. Things I’ve passed by for years and years. Merrill Hall, the connected farm below, various country stores. Really, I’ve given none of them much thought at all. And to think, if I had just stopped to learn about the history behind these buildings, I could have been writing and sharing all along. Better late than never, I suppose.

The Connected Farm

About three years ago, Laura and I decided to exchange used books on Valentine’s Day. Decades had passed and so many cards and gifts had been exchanged since we had initially gotten together – things needed to be mixed up. We needed freshness. I still make dinner and we still drink wine (I even made chocolate covered strawberries this year), but our favorite activity is to now visit the used bookstore in town to find a few $4 books to give to each other. So that’s what we did this year. And on the way, we passed by the prettiest farmhouse on the prettiest of days.

This one happens to be located near the lake. The portion of the house I photographed is called either the back house (carriage house) or barn, depending on its purpose or use. It’s attached to a long center portion of house, usually the kitchen, and then the primary, or original, part of the house, called the farm house. Believe it or not, farm houses and barns weren’t always set up this way. Originally, the barn was separate from the farm house and the two structures were connected later on. It’s called a connected farm and similar instances of it are located all over Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. We’ve driven by these types of homes for years and I’m ashamed to admit it, but I never actually gave the reasoning behind their construction much consideration.

So why are these farm homes connected to back houses and barns like they are? It’s got to do with working during the winter. And mind you, before I go any further, know that New England isn’t the only place you’ll find long rambling homes like these. They’re also common in England and Wales. Although, theirs look somewhat different than ours.

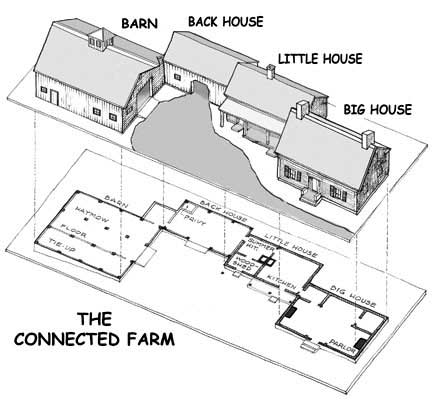

The New England connected farm dates all the way back to the 1700s. If you’ll remember my country store post where I discussed Captain George Popham, you’ll recall that the colonists fled from Maine after only one harsh winter. Needless to say, they didn’t appreciate the weather. Well, it didn’t take long for them to return and from then on, they decided that if they were going to make a go of it, they were going to have to devise ways to deal with working through the winter weather. If you’ve never visited Maine in January or February, I can tell you that maintaining mobility in the frozen, hard-packed snow can become burdensome and overall, it’s rather challenging to deal with. It’s for this reason that farmers in the 1700s began connecting the various parts of their homes. The big house (farm house) was connected to the little house (kitchen), which was connected to the back house (carriage house), which was connected to the livestock barn. With everything connected, the farmer and his family could maintain mobility all year long. And what’s more, all of the structure’s doors were situated on the south side of the home to allow for snow melt during the sunny winter days. The south side of the home is also protected from the northerly winter winds. Fascinating? I think so.

Take a look at the typical layout and then, if you’re interested, you can read further here.

When we first moved to Maine ten years ago, we began hearing the phrase “door yard.” I had no idea what that was. Back in my home town, I remember calling different yards different names, such as back yard, side yard, and front yard, but never door yard. And to be honest, up until writing this post, I had no idea what a door yard was. I know what it is now.

Although this four-part arrangement might sometimes appear haphazard, most nineteenth-century New England connected farm buildings shared similar patterns of spatial organization and usage. Most farms were aligned at right angles to the road with the major facades of the big house and the barn facing the road. Farmers then oriented their line of connected buildings to shelter a south- or east-facing work yard, called the door yard, from north or west winter winds.

Thus the formal front yard was an extension of the architecturally formal big house, the working door yard was an extension of the workrooms in the little house and the back house, and the animal barnyard was an extension of the barn. The front door faced towards the milder and sunnier south, regardless of where the road lay. Source.

An excellent description of a door yard, or dooryard, can be found above. A more informal one would look something like this:

Dooryard: The yard just outside your entrance door. Most commonly used by mothers to remind their children where to leave their shoes. Example: “Don’t track that snow into the house! Leave your boots in the dooryard.”

I think this is what most Mainers refer to when they use the term because most Mainers I know don’t live in connected farms. They live in much more modest homes that have…well, doors.

To wrap this up, I’ll share a beautiful connected farm house that’s located in Denmark, Maine.

The American Revolution

It didn’t take too long for me to find the book I wanted. As I mentioned in my recent post, Twice Sold Tales, there were more than enough books from which to choose. I found three candidates and settled on one. It’s called The American Revolution – First Person Accounts by the Men Who Shaped Our Nation by T.J. Stiles. I believe it’s got promise. It certainly describes an exciting era that shares a level of drama that’s somewhat comparable to the modern day.

In the late 1700’s, in a strip of colonies on the edge of Western civilization, a small group of individuals changed the world. Against overwhelming odds, they created a nation, defended an empire, and voiced ideals that inspire us to this day. In The American Revolution, historian T. J. Stiles tells that remarkable story through the words of those who lived it. Stiles, author of the award-winning Jesse Last Rebel of the Civil War, brings together contemporary letters, diaries, and essays that capture both the impassioned arguments and dramatic events. These first-person accounts, woven together with Stiles’s own fast-moving narrative, provide a beginning-to-end history of the Revolution, from the first murmuring of dissent, to the roar of the battlefield, to the final diplomacy that concluded the War of Independence.

If you told me one year ago that I’d be interested today in the American Revolution, I wouldn’t believe you. To most, it seems like a somewhat dry piece of history. Perhaps tried-and-true historians would appreciate the period of time, but the average person – not so much. So why am I?

During the lead up to and the era of the American Revolution, there were, believe it or not, real people, living real lives. History textbooks explain to students what happened – an overview. A boring overview. Personal letters, notes, and memoirs, on the other hand, shared with vivid detail individuals’ personal accounts and perceptions of what happened in a much more captivating manner. Believe me when I say this: history isn’t interesting to me. But when I can connect it to the present day through locations and structures that are relevant to my own life, it becomes much more so. Just the fact that I snapped a photo of a home that might date back to the 18th century tells me that the history that surrounds us wasn’t so long ago, or, isn’t as historical as I, or we, think it is. I’ll discuss John Adams in the next section, but if you read his letters to congress and his wife Abigail, you’d likely agree that it’s very relatable to the present day. And things that are relatable are more easy to understand, comprehend, and appreciate. I believe a student of history needs those things to stay tuned in. At least I do.

I’m looking forward to reading this book and I’m sure I’ll mention it on this website. I may even share short excerpts. As you can see, I’ve got a penchant for doing that.

John Adams was a Writer

To me, three things so far stand out about John Adams, our second president. He loved to write and considered it his duty, he understood, was intimate with, and knew to appreciate good taste, and he had an unwavering devotion of the value of freedom. Beyond that, he was an utter workhorse, who, I’m not sure, knew how to do much other than it.

I’d like to keep this section brief. I’ll share a few snippets of text from my John Adams book to illustrate what I referred to above, just to give you an idea of how dutiful this man was.

This first snippet describes the volume of Adams’ writing. I couldn’t imagine anything other than him enjoying the task.

But much the greatest part of the outpouring was to congress. From his room on the Rue de Richelieu, Adams issues almost daily correspondence, writing at times two and three letters a day, these addressed to President Samuel Harrington and filled with reports on British politics, British and French naval activities, or his own considered views on European affairs.

With still no response from congress, after some 46 letters, he kept steadily on. “I have written more to congress since my arrival in Paris than they ever received from Europe put it all together since the revolution began,” he told Elbridge Gerry without exaggeration. Franklin by contrast rarely wrote a word to congress. By late July, Adams had produced no fewer than 95 letters – more than congress wanted, he imagined – and never knowing whether anything had been received.

This second snippet illustrates Adams’ appreciation for aesthetic and beauty, even if it has the potential to seduce, betray, and deceive.

Living at the center of Paris, he was able to see more of the city than ever before. The busy Rue de Richelieu was one of the most fashionable streets and the Hotel de Valois , at 17 Rue de Richelieu, a premier residence. John Quincy would remember it as “magnificent.” Close by were the gardens of the Palais Royal and the Tuileries, which, with their statuary, Adams thought beautiful beyond compare. On days when the boys could be with him, they walked the gardens and much of the city. He took them on his rounds of the bookshops and the Left Bank. They toured the Jardin du Roi, with is celebrated natural history displays. How long would it be, Adams wondered, before America has such collections.

“There is everything here that can inform understanding, or refine the taste, and indeed one would think that could purify the heart,” he wrote of Paris to Abigail. Yet there were temptations. “Yet it must be remembered there is everything here, too, which can seduce, betray, deceive, corrupt, and debauch,” and in order to see his duties , he must steel himself.

And this final snippet, by far the most striking of all, illustrates Adams’ devotion to the concept of freedom.

I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study paintings, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.

I take this from the last snippet: I must fight the battles that need to be fought in order to allow others to educate themselves. They must educate themselves to such a degree as to allow an economy and freedom to flourish. Within that economy, the arts can flourish. John Adams was certainly a wise man.

This brings me to the end of another post. I sincerely hope you enjoyed it and, if so, I invite you to leave a comment down below to let me know your thoughts. It’s always nice to get feedback on the things I share.

Below are a few questions I’d like to ask you:

- Would you like to receive these posts via email? If so, you can sign up here. I send out a new post every single Monday morning, bright and early.

- Are you new here? Are you interested in reading through my entire list of posts that go way back? If so, you can start right here.

If you did any of these things, I can tell you right now that you’d truly make my day. Thank you so much and with that, I say adieu. Or at least, until next time.

PS – Can you do me a huge favor? Can you please share this page with someone you think might enjoy it? Here are some links to help you do that. Thank you!

Love your post, though I never considered the history of the American Revolution dry! Probably the most fascinating part of our past – and John Adams was amazing.

Thank you very much. I guess I was referring to those who aren’t interested in history much as a whole. I agree with you though, I’m not sure how anyone can find this particular slice of history remotely uninteresting. Thank you for the comment!