Contained in this post is a collection of separate articles, questions, and answers I’ve written that discuss the world of economics. If you’d like to contribute, please do so in the comment section below. I welcome all opinions. Thanks!

What is Economics?

Let me ask you a question. How would you like to live in a mansion? I thought so. How would you like to have a staff of 20 people, waiting on you hand and foot? Perhaps a chef to make all of your meals, a masseuse to massage you three times a day, someone to clean your house, and maybe ten Golden Retrievers to run around and play with you all day. Well, when you’re not getting your massages. I haven’t even mentioned the cars, motorcycles, and private jet yet. I was getting to that.

If I had to guess, I’d say that most of us would love to have all of this. There’s only one thing standing in the way. Can you guess what that is? You got it. It’s money. Most of us don’t have the money to pay for even a fraction of what I mentioned above.

Let me ask you another question or two. Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone on earth had what I just described above? So, besides yourself, every single one of the seven billion humans inhabiting the earth would live in their very own mansion with servants and pools. And what if everyone also owned enough land on which to really have a good time? So much land that each person lived on a piece of real estate the size of Texas. Yes, that’s right. Every single person would live on a piece of property that’s the size of Texas. And have 20 people working for them. And have many, many dogs. And pools, And chefs. Oh yeah, and motorcycles.

Can you guess what the problem with this scenario would be? If you said that there’s not enough land in the world (of the size described above) for everyone to own, you’d be correct. Also, if everyone was living in a mansion doing all these things, what about the servants? Wouldn’t they have their own mansions? When would they be serving you if they had their own servants. And who would be making the airplanes if we were all partying all day? You see the problem here. Not everyone can have everything because it just wouldn’t work. The entire idea is unsustainable.

All of this thinking leads me to a definition I’d like to give you. It’s a definition for economics. Here goes:

Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity.

Now that we know the definition of economics, let’s point out what’s scarce in the examples I gave you above. The first thing that’s scarce, we already discussed. That was money. I don’t think either you or I have the money to pay for the employees or dogs. But beyond that, as mentioned above, there’s not enough land on the planet to give everyone something the size of Texas. And furthermore, what about people themselves? If each one of us were to have 20 employees so we could goof off all day, when would the employees be goofing off? They’d have their own employees, etc… And then, what about time? And resources to make all the stuff I mentioned? And where would we get 70 billion Golden Retrievers. I think you get the point here. There’s scarcity of goods, services, labor, tools, land, and raw materials on earth and economists like to think about how that affects personal, family, group, governmental, and business decisions.

All of this brings me to a new thought. If there’s scarcity on earth, what actually causes that. What precisely makes something scarce? Say there was a copper mine that, if mined, would give us 100 billion tons of beautiful copper? Would copper be scarce? What if the mine only gave us an ounce of copper? Would copper be scarce? The answer to these questions depends on how much copper is wanted or needed in comparison to how much is available. If no one wanted or needed copper for anything, then even an ounce wouldn’t be scarce. If we had 100 billion tons of copper available to us, but needed twice that, then it would be scarce. Whether or not something is scarce depends entirely on us.

Can you guess which is the most scarce resource on earth? I’ll tell you. It’s time. Time is the great equalizer because no matter who you are, how much money you have, how good looking your face is, we all have exactly the same amount of time in every single day. No matter what. And that’s why so many other areas are mentioned in relation to time. Think about the measure of productivity here. How many widgets can one employee make in an hour? There’s that time thing again. More on this later.

If scarcity is an issue because humans are always in want or need and because resources are finite, how would we deal with it? I would venture to say that we simply wouldn’t get everything we want. To deal with the money issue, most of us would likely have to forgo the mansion and the related toys. And to deal with the labor issue, we’d probably give up the employees. And to deal with the space issue, we’d most likely have to let go of the property the size of Texas. So because there simply isn’t enough of what each of us wants, we’d be forced to make concessions. We might not like those concessions, but that’s the way life is.

The terrible thing is, scarcity is a very real thing. There are some folk out there who ask questions such as, “Well, why don’t we just give people what they need?” I guess the answer to that would be, “Because we don’t have enough to give them.” Economics is a deeply complex subject that, even when studied for years, can still surprise the best of us. Consider hunger across the world. Housing. Healthcare. All the other things that can allow someone to live a better life. Why don’t these people have all of what they need? It’s all because of scarcity.

To truly understand the concept of scarcity, we’ll need to discuss this much more deeply. I hope to write about this topic in its entirety very soon. In the meantime, let me ask you what the most scarce thing in your life is. What do you feel that you need more of? What do you think should be more available in society as a whole?

How Information Affects Economics

Information is economics and vice-versa. You can’t have economics if you don’t have information. I want you to again think about this definition for a moment:

Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity.

Think about how economics affects your everyday life. Would it be economical for you to purchase a huge bus in which to drive to a nearby market one time or would you be better off if you bought nothing? Perhaps walking would be best. Which route should you take to that market? The one that zigzags all over town or the one that simply cuts through a small piece of property? When should be go to the market? During a torrential downpour of rain or after?

These all seem like easy questions to answer. First, of course you wouldn’t go out to by a bus just to go to the market once. That’s just silly and a waste of time and resources. Next, of course you wouldn’t zigzag all through town to get to the market when there’s a shorter route. That’s wasting precious time. And finally, of course you would wait until after the rain stopped before you went to the market, lest you get wet. Each of those decisions is fairly obvious. Or are they? What if you had to bring 35 people to the market with you and you were being paid $1 million to do so as fast as you could? Then, perhaps a bus would be a better option. Also, what if you had other errands to run, besides going to the market, so zigzagging through town would actually be more efficient than skipping those errands altogether? And finally, what if the man of your dreams asked you to meet him at 3pm sharp, no matter what, while you’re walking to the market? What if that was the time it was raining? Would you still do it? Your entire life may hinge on this decision.

As you can see, the more information you have, the better the decisions you can make. Economics is all about making the best possible decision from your available information. Whether or not something is economical is based off that information. A passenger plane flew the shortest possible route across the ocean from the U.S. to England. Was that short route economical? It would seem so. What if there was only one person aboard the plane? Still economical? I’m sure you get the point. Without data, you’re lost at sea. This is why so much of economics is based on the gathering of data. If you think about it, if there was a way to gather all the information in the world, you’d likely be able to make what’s referred to as a perfect decision. After all, there would be no unknowns. The truth of the matter is though, rarely do we have all necessary information. And because of this, we called our the information we do have, imperfect. Despite this, we still go ahead and make decisions anyway. We simply adjust as we go and gather more data.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how the internet and social media have changed the world. I’m not sure if it’s for the better or worse, but that’s irrelevant. What I’m referring to here is the impact the internet has had on economics, the economy, and whether or not we deem something economical in our own lives. Today, we’ve got so much more information with which to make decisions than we’ve ever had. Think about something as mundane as scheduling a baseball game. Years ago, each game would be scheduled at the beginning of the season. Let’s say they were set for Wednesday evenings at 6pm. If everything went without a hitch, the weekly games would take place on time. But what if something went wrong and a game needed to be delayed? Either no one would know about that and they’d show up at the regularly scheduled time or someone would have to call each player, which could take all day, as you can well imagine. Today, all that someone need do is make a quick post on the team Facebook page telling everyone else that the game needs to be delayed. That’s it. Everyone would know in an instant. Examples like this are endless, but suffice to say, the internet and social media have turned the world of economics in its head.

I’ll be doing a lot of writing in this forum that focuses on how the dissemination of information impacts economic decision making. How does the processing of information have an impact? How does understanding human behavior affect economics and the markets as a whole? And how does the speed of gathering this information affect these things as well? If you’ve got anything to add or if you’re an economics enthusiast as I am, I welcome you to chime in down below.

How to Deal With Scarcity

Throughout my life, I’ve heard different people say things like, “Well, why don’t we just make more of such and such?” Or, “Why don’t we just feed everyone as opposed to a select few?” I’ve even heard, “We should just make it so everyone is rich so everyone can have it all.” I cringe when I hear these types of things because while it may seem possible to actually enact these types of ideas in the short term, they’re certainly not sustainable over the long term. As you learn more and more about the laws of economics, you’ll understand why. Scarcity is the overriding factor for how much of the world works.

There’s an age old question out there that lingers over the heads of even our brightest thinkers. How do we solve the problem of scarcity? How can we as a society give more with less? How can greater and greater numbers of people enjoy the fruits of their labor while offering less and less of that labor? If you think about all of the things you consume on a daily basis, you’ll quickly realize that the issue of scarcity has been dealt with quite readily through the years. At this moment in time, more people on earth have more than anyone has ever had in all of human history. Whether it be food, shelter, cars, healthcare, clothes, and even an internet connection, more people have got more while giving less. And just to hammer this point home, think about our forefathers. So many of them had to perform so much work themselves. If they wanted a house, they’d have to build it. If they wanted to eat, they’d have to grow their own food. If they wanted to wear clothes, they’d have to make them. Back in the early days, there was an endless amount of work that needed to be done. So much so that many people didn’t make it very long. They simply couldn’t survive, which is a far cry from today. While in the old days, an individual needed to possess a very wide breadth of skills, these days, an individual need only become proficient at one or two. That one or two gets them by, but how do they do that? How is it that possessing even less in the way of survival, building, mechanical, farming, or hunting skills and an understanding of how things work gets someone more than they’ve ever had in all of history? That’s easy. It’s not that they can’t learn all of these things. It’s that they don’t need to. There’s a very important concept referred to as the division and specialization of labor that has allowed humankind to progress to heights never seen before. It’s smart. Very smart. And we’ll discuss it in the next section.

What is the Division & Specialization of Labor?

This is a fun topic. Let’s pretend for a moment that you are a shoemaker. All day, every day, you work in your shop making the best shoes in town. You craft the soles, weave the laces, prepare the leather, bend and fold the material, glue the pieces, and sew everything together. From start to finish, it takes you two weeks to make one pair of shoes. Luckily, people love your products and pay a hefty fee for them. You do wonder, however, if there is a better way. You sometimes feel as though you’re spreading yourself too thin and that your process is inefficient. You also wonder if you’re not as good at preparing each piece that goes into each shoe as you could be, since you don’t really specialize in anything. You are good at the entire process, but you aren’t great at any one step.

This is where the division and specialization of labor comes into play. Adam Smith first wrote about this concept in 1776 in his book titled The Wealth of Nations. While economics can been discussed for centuries before Smith touched upon the topic, he was the first to delve into it so comprehensively. Smith laid out the process in which producers can more economically and efficiently manufacture their products. Essentially, he claimed that if a comprehensive process was broken down into pieces (divided) and each piece was handed off to an individual or a team (specialization), those individuals or teams could do a faster and better job of doing what they’re responsible for than one person ever could. When one person is responsible for too many tasks, they suffer from what I described at the beginning of this post. They’re worn thin and don’t so as good of a job as could be done.

Now let’s pretend that, as a shoemaker, you hired a few friends to help out in your shoemaking endeavor. Instead of you doing everything and being great at nothing, one person crafts the soles, another weaves the laces, another prepares the leather, another bends and folds the material, another glues the pieces, and another sews everything together. This leaves you, the business owner, the freedom to grow the business. With this division and specialization of labor, the production time of each pair of shoes goes from two weeks to a half hour. As you can imagine, the shoes are of the same quality or better and you’ve got many more of them to sell. You’ll be going global in no time.

What’s really interesting about this concept is how often it’s applied to our own lives without us even realizing it. Just the fact that we drive cars that we didn’t build is proof of the division and specialization of labor. We also don’t make the medicine we take. Or deliver the letters we write. Other individuals and teams have chosen to do all that. We specialize and take care of what we’ve chosen to do so these other people don’t need to. It’s sort of a miraculous and ingenious system.

Next time you go out to dinner, take a look around to see how many pieces of labor the entire process of running the restaurant has been divided into. I’m sure you’ll be surprised. From the host to the waiter or waitress to the chef to the manager, it’s a rather complex process. And as you sit there eating your lunch or dinner, think about how complex it must be to run a Fortune 500 company. Say you own ExxonMobile – a company that drills for oil and then refines that oil into a variety of different products. In companies like these, there are thousands and thousands of processes that have been divided up and specialized in through the decades and centuries. Imagine trying to do everything yourself. It’s just not possible.

How Division of Labor Increases Production

According to Adam Smith and his book, The Wealth of Nations, when a process, whether it be a service or the creation of a good, is broken down into separate tasks to be completed by distinct individuals, a greater output can be expected. If you take the shoe example in the previous post on this topic, one shoemaker can only produce a marginal amount of shoes per day by himself. If the individual tasks and processes that went into creating each pair of shoes were divided between multiple individuals though, that number can be compounded greatly. In The Wealth of Nations, an example of making pins was given. Smith contends that while a group of men performing distinct tasks in an effort to manufacture pins can create 48,000 pins per day, if each man were to take on every task necessary to make pins by themselves, they’d only be able to make 10-20 each. These examples beg the question; How can dividing tasks between workers result in so many more products produced? Why is it that production of an item from start to finish by one individual is so much lower? There are three primary answers to these questions.

Specialization – Let’s go back to the shoe making example as it’s easier to understand than the pin making one Smith used. What if some parts of the process of making shoes was somehow more conducive to certain people who have certain characteristics about them? If making shoelaces requires a very intricate and delicate touch, do you think someone with small, thin, nimble fingers would be better at tackling that chore or rather someone with big strong, but clumsy fingers? Probably the delicate ones. What if folding of the leather required great hand strength? In this case, the strong hands would prevail over the delicate ones. What if one or two steps of the process called for a vast amount of training and education about the process? Would someone who has little to no training or education be suitable for these particular tasks? No, they’d only hamper the process, slowing things down greatly. There’s a term referred to as specialization that allows for those who have an interest in, training, or innate abilities or talents to take advantage of situations where they may be able to put those assets to good use. It can be said that because of their assets, they have an advantage over others who would attempt the same or similar chore.

Core Competency – When an individual (or company) works one job with a limited scope, they tend to become extremely proficient at it. Think about workers on an automobile assembly line. If one worker were to be trained how to install transmissions and did very well at that job over time, he would be able to make the installations with greater efficiency than if just one person were responsible for transmission installation, windshield installation, as well as dashboard installation. Oftentimes, when an individual is responsible for just one or a limited number of tasks, they learn the best ways to go about performing these tasks as economically as possible, enhancing the organization as a whole.

Economies of Scale – When workers can focus on their jobs and can become more proficient at them, more units are able to be produced. And the more units produced, the more specialization can take place. As production, division, and specialization increases, costs per unit fall. This is what we call economies of scale. As the scale of units of production changes, so do costs. In terms of scarcity, entire societies and nations have benefited from the more efficient methods of production that this concept encourages.

How Does Specialization Affect Trade & Markets?

The division and specialization of labor is great, but only if you’ve got buyers for the products you’d like to sell. You can divvy up a process as much as you’d like, and yes, you’d have a much more productive and efficient operation, but what good is all that if you don’t have a market in which to sell your products? Not very good, that’s what. Specialization makes only as much sense as the market behind it allows. If employees, or those who are engaging in specialized tasks, get paid for their efforts and are able to go out to purchase the goods and services of others, they can support to division and specialization efforts of others. This is called trade and this is what’s required for a functional economy.

The beauty of the division and specialization of labor is that only those who are engaging in the process of creation need to understand the specifics of the task. Sure, the owners of the business and the engineers who have initially created the process need to know too, but by and large, it’s the person or group who are responsible for completing the task who need know most about it. If you think about it, if we drive a car, we don’t need to know about every single function that makes it work. We simply need to get into it and drive. If we play baseball, we don’t need to know every single step necessary to make a baseball bat. We just swing and hit the ball. In fact, we hardly need to know anything that goes into making the products we use every day. All we need to know is that they exist and how to use them. We don’t need to know the processes involved and we don’t need to learn all the skills required for production, that’s for sure. It’s the market that allows for all of what we know to function smoothly. All we need to perform is a tiny sliver of labor and to get paid for that. Once paid, we can trade our money for all the tiny slivers others have contributed to the same market. When combined, the tiny slivers and the market as a whole creates what we understand to be the economy.

Why Should I Study Economics?

The study of economics is a very philosophical endeavor. Rarely is there a right or wrong course of action to take. In truth, the entire study is full of question. Yes, there are many mathematical calculations that can be made, but there’s a lot of human input that goes into those calculations as well. Attempting to decide what’s best for a specific group of people, company, or world at large requires much thought and a strong understanding of cause and effect. Without these things, economics wouldn’t do much good.

Every day, we read comments on the internet that make absolutely no sense. “We need socialism now!” “God bless capitalism!” “The communists are coming!” “The end of the dollar is near!” Have you ever noticed that most of these people who make these statements and claims have no idea what they’re talking about? Have you ever noticed that they simply parrot what they’ve read somewhere else online? Has one who comments ever offered any supporting documentation for their claims? Would they even know where to look for documentation? If you’re reading this post, I can only assume you’re interested in studying economics, or at least learning a little bit about it. That’s fine. You’re right for doing so. Just beware, the study of economics isn’t all about boring facts and figures. It’s actually mostly about using your brain to unpeel the layers of small puzzles. As humans, we identify the puzzles in our world and as amateur economists, we use the tools we learn about and create to figure those puzzles out. The study of economics is about coming to sensible decisions. Conclusions, if you will. Why is socialism better? What is socialism anyway? Why is capitalism better than socialism? What’s the economic structure of communism? These are all questions you’ll likely answer as your studying continues on. Of course, these are a tiny fraction of a much larger whole, but just this little bit will give you a greater insight as you scroll through all those ridiculous comments on YouTube.

Here are a few core reasons you might want to study economics:

1. Economics is everywhere. Virtually every single global problem you’ve ever heard of has an economic aspect to it. A hurricane in Texas? A war in Africa? Unrest in Portland? A government overthrow in Europe? Global warming? Each of these problems requires a solution. And any solution is going to need to be economically sound. If you’d like to be part of that solution, you’re going to need to understand the problem. That’s where economics comes in.

2. Vote with your brain. How often have you heard of friends and family speaking about economics around election time? Probably not very often. For me, most of my family speaks with their hearts instead. While this is fine and we all want the best for everyone, if we all voted with our hearts only, very few issues would ever get addressed. Government is about allocating finite resources to the citizens of a nation for the betterment of those citizens. If we elect a government that’s good at campaigning on absurd promises as opposed to what’s actually feasible, we’d just make bad problems worse. We’ve all heard of bum politicians making corrupt or terrible financial decisions. A good politician is one who fully understands the issues at hand and who has the sense to address them properly. By studying economics, you’ll gain the ability to identify these politicians.

3. Understanding economics helps you be a better thinker. Studying economics isn’t all about learning what others tell us. It’s about thinking for ourselves. Again, the study of economics can give us the tools we need to solve puzzles. Some of these puzzles haven’t even presented themselves yet. By delving into a topic like this, you’ll think differently about the world. You’ll become more well-rounded. When you read articles and listen to people speak, you’ll pick up on terms and concepts that are helpful in making good decisions. You’ll also be able to identify the frauds. You’ll gain the ability to pinpoint an issue in a situation and you’ll be able to draw on your knowledge to solve it or at least understand it in a more lucid way. Current events will become more easily understood and personal decisions won’t be as tough to make.

Again, while the study of economics won’t always give you the answers, it will give you a framework from which to draw your own conclusions. It’ll also bring forth many different options you may have not known were available.

Key Concepts for Studying Economics

Well, I made it to the end of chapter one of my economics textbook. By the way, if I haven’t mentioned it before, it’s called Principles of Economics. It’s a really great book and I’ve already learned a lot from it. I enjoy reading what it has to say and then turning things into my own words to share here. This strategy helps me learn. If I were to simply read through the book with no writing afterward, I’d probably not retain very much. It’s the fact that I repeat and translate that makes the concepts stick.

So what have I learned so far? Well, economics has to do with scarcity. It studies what’s abundant in this world and what’s not. Those who study economics seek to solve the problems that scarcity causes. One major method for dealing with scarcity is to employ something called the division of labor. Basically, when someone specializes in one or a few tasks as opposed to many, they’re able to use their talents, learn, and become more efficient at that task, rather than remain inefficient at too many tasks. When someone is able to focus on just one (or a few) task(s) and get paid for it, they’re able to use that income to purchase what others have produced. When everyone does this, it’s called a market. When people divide their labor and specialize, it allows for a few different things to occur: individuals can focus on what they’re good at, individuals can completely learn about a given task and find ways to do it better, a system of individuals can take advantage of something called economies of scale. And finally, by learning about economics, I’m able to become a better, more well rounded individual. One who understands the intricacies of the world and one who thinks more clearly and in a more level-headed way.

At the end of chapter one, there are some questions to answer. I thought I’d do that here.

Chapter One Questions

1. What is scarcity? Can you think of two causes of scarcity?

Scarcity is when wants and desires outweigh production or available supply. There are many reasons for scarcity. Lack of natural resources, laziness, inability to produce, inefficient production, lack of human capital. Whatever the reason for the scarcity, the fact remains that a resource or resources are limited. On the flip side, even when resources are abundant, it appears that demand rarely wanes. So to answer the question, the two reasons for scarcity are lack of resources and inherent demand.

2. Residents of the town of Smithfield like to consume hams, but each ham requires 10 people to produce it and takes a month. If the town has a total of 100 people, what is the maximum amount of ham the residents can consume in a month?

If there are 100 people in the town and it takes 10 people to produce one ham, it would take 100 people to produce 10 hams in one month. Since the demand for the hams is consistent and limited only by supply, the residents’ consumption is limited by the production of the 10 hams. That’s all they can eat per month. In order to increase this number, they would need to increase the human capital of their town or find a more efficient method for making the hams.

3. A consultant works for $200 per hour. She likes to eat vegetables, but is not very good at growing them. Why does it make more economic sense for her to spend her time at the consulting job and shop for her vegetables?

If this consultant is already making $200 per hour, it’s assumed that she’s good at her job and that there is a demand for it. Growing vegetables is time consuming. Certain skills are also needed. Vegetables don’t cost that much money to buy, so it would be in the best interest of the consultant to work at her consulting job to earn the money to purchase the vegetables. By her attempting to grow her own vegetables, she’d lose out on opportunity cost from her consulting job. And there’s no guarantee of success while growing her own vegetables either, which would end up being a total waste.

4. A computer systems engineer could paint his house, but it makes more sense for him to hire a painter to do it. Explain why.

Same answer as above. If the computer systems engineer can make more money by doing his primary job, then it would make more sense to hire someone to paint his house. Unless, of course, the painter is charging a fortune, or more than the computer engineer earns at his job. In that case, he should paint his own house. But this second answer goes against the question. In it, it was stated that it makes more sense for him to hire…, so I’ll stick with my first answer.

5. Give the three reasons that explain why the division of labor increases an economy’s level of production.

For complete answer, look here. The three reasons are comparative advantage, core competency, and economies of scale.

6. What are three reasons to study economics?

For complete answer, look here. The three reasons to study economics is to understand the economic dimensions of world problems, to understand budgets, regulations, and laws and to vote with the best interests of the general welfare in mind, and to become a well rounded thinker.

Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics

You’ve likely heard of economics, but have you heard of microeconomics and macroeconomics? If you’ve taken a business class in high school or college, you probably have heard of either of these two. They’re both closely related to one another and believe it or not, one couldn’t exist without the other. They’re symbiotic, if you will.

Economics doesn’t discriminate. It doesn’t care if you’re young or old, rich or poor, or whether you have a job or not. It’s the study of the economy and everything contained therein. It studies production and the impact that production has on the planet; the well-being of its inhabitants as well as the well being of its environment. Economics deals with pollution, developing nations, labor unions, government spending, taxes, and so much more.

Contained within the broad realm of economics is two subsets: microeconomics and macroeconomics. As stated above, one relies on the other. Microeconomics is the study of the smaller aspects of the economy, such as the individual, households, small businesses, large businesses, organizations, and so forth. Macroeconomics is the study of the entire economy as a whole. It delves into areas such as overall production, general unemployment, inflation, government spending and debt, national exports and imports, and so forth. Both of these areas rely on one another, as one couldn’t exist in absence of its counterpart.

When studying economics, it’s critical to understand the roles both the macro and micro subsets play. The best way to put things in perspective is via an example. We’ll use a household as this example.

Let’s say we’ve got a multi-functional household. There are various parts and they all work together. One person in the home may deal primarily with arranging the furniture, purchasing the groceries, making dinner, deciding which wallpaper goes in which bedroom, and how best to manage the flow of everyday life inside the structure. Another person may take an entirely different view – a more holistic and overall view as opposed to one so detailed and minute. This person may deal with paying the property tax, making sure the roof of the home is in good order and doesn’t leak, making sure any snow is cleared from the driveway so traffic can enter and exit, and making sure the home is safe and secure. As you can see, both of these approaches to managing the home are useful and necessary, but one focuses much more on the daily goings ons, while the other focuses much more on making sure there’s an actual home to house the inhabitants. One is like an umbrella while the other is like the person under the umbrella. Both important. Both necessary. Both different. They’ve got different viewpoints.

With both economics and running a household, it doesn’t matter which aspect you look at more. What is important is that you appreciate both as functional parts of the whole. In the home, what goes on inside is just as important as what goes on outside. You’d have no reason to have a home if nothing occurred inside of it. Just like you’d have nothing to do inside of a home that wasn’t safe, couldn’t be accessed because of snow, or if it didn’t have a roof. When it comes to micro and macroeconomics, when the overall economy is healthy, more small businesses hire people and individuals make more purchases. But if people aren’t buying, then small businesses won’t do well, which would affect the entire economy as a whole. It’s like a ying/yang thing.

Microeconomics & Macroeconomics Descriptions

Micro

Households only have a certain amount of money to spend each year. How will they do so? What goods will they buy? What services will they seek? Will those in the household be able to afford these things with money they earn or will they have to go into debt to purchase them? Where do individuals work? What made them decide to seek employment at these places? Do they work full time? Part time? What types of retirement savings do those in these households have? How much do they spend on credit cards? What’s the average or cumulative consumer debt across the nation?

When it comes to business, what types of products are being sold? How many will each firm produce? Is there a market for these products or services? What will the prices be and what determines those prices? How many employees will be employed by each business? Will a business use debt to operate? Money on hand? Savings? Investments? Do these businesses plan on growing, shrinking, closing down? All of these questions are asked under the umbrella of microeconomics.

Macro

How many goods and services will the entire nation produce? What’s the overall level of employment nationally? How much money does each person of the nation earn per year, per capita? What’s the standard of living? What causes the overall economy to increase in size or decrease in size? What factors cause its acceleration or deceleration?

Within the realm of macroeconomics, many areas are studied and goals for a healthy economy are produced. Goals such as maintaining a specific standard of living, a certain level of unemployment, a particular yearly inflation target, and others. When it comes to meeting these goals, a variety of tools are used. Tools such as the tightness or looseness of bank lending, Federal Reserve interest rates, and the required function of the capital markets.

A lot goes into the macroeconomic picture, from the central bank to the United States government, to spending, and taxes. All of these things work together to set the stage for a well functioning economy.

Microeconomics & Macroeconomics Questions

1. What would be another example of a “system” in the real world that could serve as a metaphor for micro and macroeconomics?

There are many examples that can be used as metaphors. One might be the oceans. A marine biologist may study small areas of ocean life and habitat, such as types of fish, plants and plankton off the coast of Maine. Federal and global entities may study sea level and overall temperature and pollution. The fish in a specific area would certainly be affected by the macro picture while rising temperatures and pollution levels would be less critical if no fish or marine life existed at all.

Another example might be the study of the solar system (micro), versus the study of the galaxy or universe as a whole (macro).

2. What is the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics?

Microeconomics concerns itself with the individual, household, city, state, business, and organization level economics, while macroeconomics concerns itself with federal and global issues, such as interest rates, unemployment rate, debt per household per capita and things like that.

3. What are examples of individual economic agents?

Micro: Households, workers, and businesses. Macro: Production growth, unemployment, inflation, national deficits, imports, exports, and global trade.

4. What are the three main goals of macroeconomics?

The three primary goals of macroeconomics are an increase in the standard of living, keeping low unemployment, and a low steady inflation rate (2%, according to the Federal Reserve).

5. A balanced federal budget and a balance of trade are considered secondary goals of macroeconomics, while growth in the standard of living (for example) is considered a primary goal. Why do you think that is so?

It could be because a federal budget and balance of trade are concerns of the federal government, while an increased standard of living is more of a concern of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve increases or decreases the amount of debt (currency, money supply) in our society, while the federal government merely works within the framework of the current money supply availability. The federal government can’t create money, while the Federal Reserve can, which is why it’s impossible for the government to increase the standard of living for everyone without taking on more federal debt, which the Federal Reserve issues.

6. Macroeconomics is an aggregate of what happens at the microeconomic level. Would it be possible for what happens at the macro level to differ from how economic agents would react to some stimulus at the micro level? Hint: Think about the behavior of crowds.

The aggregate of microeconomic factors could differ from specific microeconomic agent stimulus if one agent somehow decreased some sort of micro level while another agent increased a different micro level. It would sort of be like a see-saw, evening out in the middle. Also, there are many outside agents that could influence the macroeconomic picture. It really depends on how macro macro is. Is it national or global? National trade deals could heavily influence the economic situation of a nation while the microeconomic situation wouldn’t change all that much.

Economic Theories & Models

Have you ever heard about how John Maynard Keynes thought about economics? It wasn’t all data and numbers to him. It was rather much more a way of thinking. He wasn’t a big proponent of teaching what to think, but more how to think. Keynes professed that economics gives us the tools to assist us in finding the answers. We can’t learn exactly what those answers will be if we follow explicit instructions, but rather how to use those tools to come to sensible conclusions. As an example, we would never be able to learn every single bolt in every single instance that a socket wrench may be able to loosen or tighten, but we certainly can learn how to use a socket wrench in general. Learning to use the wrench would be an extremely effective endeavor when compared to attempting to become familiar with all the occasions which we might use it.

Theories & Models

Economics is an interesting sport. Let’s say someone said something like, “I theorize that A will occur if B occurs.” That would be considered a theory. A simple one, but one nonetheless. While anthropologists and biologists create theories, economists create theories of a completely different nature. The ones economists create are based not on what they see that’s directly related to something that is or that’s happened, but more on how humans interact with one another and on human nature as an entirety. These assumptions are quite different than those that say, a psychologist, might use during his or her research. And really all a theory is, is a very basic representation of something that’s much more complex. In the example I gave above, if B occurs, then A will occur, everything else has been boiled away. The complexity, if you will. What activities and data surround A and what results and anticipations surround B? The reason many of the extremities are removed when devising a theory has to do with simplicity. It’s for easy understanding. If someone can take a theory and put it to the test and it works, then they can work backwards to extrapolate the more nuanced details later on. Good theories make for good understanding. And understanding is the first step to a much more thorough look into a complex issue.

The terms model and theory are closely related. Models are more complex though. While a theory can be abstract and very simple, a model, while not representing every single detail involved, can be a more thorough representation of an economic issue or problem. And although many folks use these two terms interchangeably, you really should know the difference. Theories make a claim, while models describe how that claim may have come about.

Let’s turn to models for a bit. You see them everywhere. Have you ever seen a brand new car design that’s bee made from clay? That’s a model. Have you ever seen a cityscape made of board and plastic? Architects oftentimes create these to represent something they intend to have built. Creating a small scale model of something is very helpful to express an idea to those who may not think about the subject on a regular basis. While an architect may thoroughly understand a certain concept, if someone is new to the topic, they may have no idea of what’s being expressed. A model simplifies things into bite sized chunks. All types of organizations create models in an effort to show the eventuality of a product. When it comes to economics, there isn’t necessarily a tangible output, so models represent ideas as opposed to products. And really, many other disciplines create thought models as well, from business to healthcare to science.

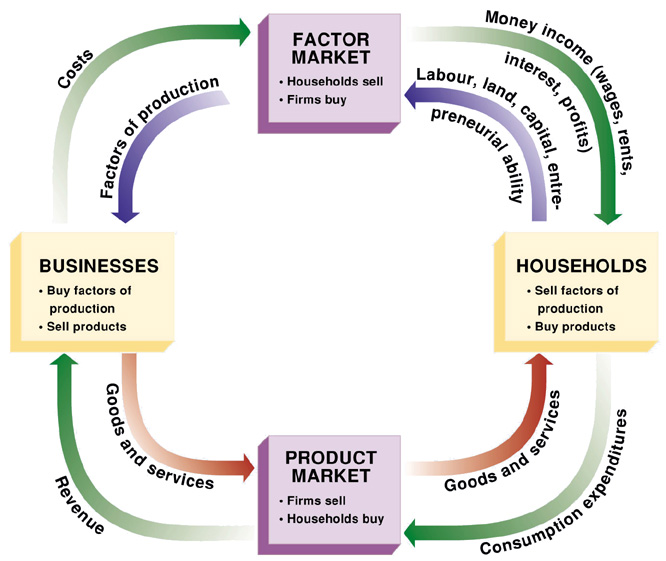

A popular economic model is called a circular flow diagram. This diagram can range from extremely simple to a bit more convoluted. He’s a good example that I sourced from the UBC Wiki.

There are two sides to this model of the overall economy; businesses and households. The model gives a great representation of how capital flows between the groups. Within the groups exist various markets, goods and services and labor being the largest and more important. Basically, households sell their labor to businesses to produce goods and services. In return, businesses sell those goods and services to the households. That’s the most simplistic view of things.

Obviously, within the actual overall economy, there are a huge number of markets as well as forms of labor. We as people don’t simply make widgets for business for those businesses to sell back to us. As explained in the specialization of labor post, many different people engage in a wide variety of tasks inside the economy as a whole. Businesses divvy up the produced products and services and sell them back to either other businesses or households. The buyers of the services oftentimes have no participation in the production, but their participation is included in the overall market. The model economists use to represent this flow of goods and labor simplifies the entire process so it’s easy to understand for those who aren’t intimately involved.

As economies grow, models have a tendency to become more complex. While this model of the general economy is rather simplistic and straightforward, it can just as easily include a wide variety of businesses and markets, such as government, business to business, and service markets such as those found in the financial arena. It could also describe the global economy, which would complicate it even more.

Questions & Answers

1. What is an example of a problem in the world today, not mentioned in the chapter, that has an economic dimension?

There are countless answers to this question. Basically, an economic problem exists when an individual or a group doesn’t have the resources to either produce something or to pay for something someone else has produced. On a local scale, it would be the individual who can’t afford to eat or to pay for housing. Or, individuals who don’t have the skills or will to contribute to the labor market. On a national scale, it would be those who can’t afford to pay for health care. Or, a segment of the population that is underutilized due to their inability to get proper education or health care. On a global scale, it would be a nation that’s land-locked (lack of trade routes) or that doesn’t have the natural resources to compete in the global marketplace. Or, one that can’t afford certain medical drugs that may help its population with certain epidemics or pandemics.

2. How did John Maynard Keynes define economics?

Keynes defined economics in this way: “Economics is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessor to draw correct conclusions.”

3. Are households primarily buyers or sellers in the goods and services market? In the labor market?

Households are primarily buyers in the goods and services market. We, as individuals, purchase what we need for everyday life. As for the labor market, households are primarily sellers. We, as individuals, sell our knowledge and labor to industry and business in return for money in which to purchase goods and services.

4. Are firms primarily buyers or sellers in the goods and services market? In the labor market?

Primarily, firms are sellers in the goods and services market, as they provide goods and services to households and other businesses. Although, on a smaller scale, firms do purchase goods and services from individuals and other firms. This is called business to business sales.

5. Why is it unfair or meaningless to criticize a theory as “unrealistic?”

It’s unfair to deem a theory unrealistic in economics because economic theories are created to help explain something that may occur based on human nature or interactions between humans, as opposed to something that has already occurred. And as we have seen recently, pretty much anything can happen in the realm of humanity.

6. Suppose, as an economist, you are asked to analyze an issue unlike anything you have ever done before. Also, suppose you do not have a specific model for analyzing that issue. What should you do? Hint: What would a carpenter do in a similar situation?

Personally, I would first come up with a general theory as to what’s happening and then I’d get more specific with a model to describe the occurrence in more detail.

Economists want to know answers. When they encounter an issue, they peel through the layers of their minds to find the model or theory that aligns closest to what they face. With the proper model in hand, they attempt to understand what’s in front of them. In general, for more complex issues, most economists will develop a theory as to what’s going on before coming to a conclusion. While in other disciplines, this process may be reversed, it’s this way for a reason in this one. Complex economic problems need to be seen and understood before delved into. To see an issue, economists use charts, graphs, diagrams, and equations. This is true for both micro and macro economics. I’ll talk much more about all of this in later posts, but for right now, this is a fairly complete introduction to economic theories and models.

Traditional, Command, & Market Economies

Economies are about organization and power. Pretty much every economy on earth follows some sort of organizational pattern and has someone or someone(s) in charge of it. Whether it be highly centralized, a hybrid of both centralization and decentralization, or totally laissez faire, there’s always a pattern and always some group pulling the strings. Centralized economies have a small group at the top of the hierarchy dictating what’s going to take place and very decentralized economies leave those decisions up to the people.

We’ve been hearing a lot lately about various types of government. We watch the news and see protestors wearing pro communism t-shirts and politicians promoting socialism. Wouldn’t it be nice if someone asked these people if they actually knew what they were advocating for? What they were protesting for? What they were ready to throw away and what they were ready to replace it with? Well, in this post, I’ll attempt to add some clarity to the arguments we hear and see most often. I’ll touch on the three most common types of economic structures that we have here on earth, the traditional, command, and market economies. I’ll list each below and then talk about what makes each tick. I’ll also discuss the pros and cons of each. And by the way, when someone talks about their favorite type of government, they’re likely referring to their favorite type of economic structure. People oftentimes confuse the two.

Before I begin, let’s think for a moment about how complex all of the various economies around the world really are. After all, each economy consists of all production, all consumption, and all employment. Each person’s life is touched in some way by their own economy and sometimes by other economies globally. What individuals and groups (firms, businesses, companies) do can have a profound effect on people who are seemingly unrelated. The question must be asked, who’s in charge of all this? Who makes sure there are enough jobs for people? Who make sure there are enough people to fill those jobs? Buy those products? Fulfill those services? How does all of this hard work and planning get done? It’s no small feat. That’s for sure.

Traditional Economy – If you live in a first world country that’s popular and in the “in” crowd, you’ve likely never heard of a traditional economy. This is a very old structure that may seem rather foreign to you, depending on what you’re used to. Think about family farms that have been in existence for generations, people who eat what they produce, people who use the barter system to trade away what they have in excess and for what they need. This type of economy is quite stagnant, in that it rarely changes. People who live under this type of structure are doing things “the way they’ve always been done.” Traditionally. You can generally find this type of thing in less developed and poor areas, such as in parts of Asia, Africa, and South America.

Command Economy – In these types of economies, economic activity is highly centralized. The general population has little to say about what happens and freedoms are oftentimes quite limited. In general, an overarching ruler or ruling class makes all the decisions and hands them down to the many departments or various classes that serve them. This type of economy was prevalent in ancient Egypt, modern day North Korea, and Cuba. A few decades ago, the former Soviet Union was communist, which fell under this category. Basically, in these types of economies, the government makes almost all economic decisions. It determines how much will be produced, how much will be consumed, and what the various prices will be for everything. It also determines what the methods of production will be and how much people will be paid. Those who favor command economies argue that they are better equipped to handle fair and equal distribution of goods and services. Those in command economies discourage profit. In modern times, we see usually young college students on the streets fighting for this type of lifestyle based on equitable treatment for all. What they fail to recognize is that the general population isn’t involved in economic decisions at all. So what these people are currently fighting for, they won’t be a part of. Also, if a certain government distributes, say, health care, for example, for its citizens at no cost, that government also determines the level of care, which may be miserable. There’s no competition under this type of system either, so you get what you get. And if that’s not good enough, there’s nowhere else to turn.

Market Economy – What most modern day protestors are actually fighting for is what they already have. It’s called a market based economy. This is an economic structure that’s built upon freedom and competition. This type of economy is decentralized and while overseen by a government or governments, it’s left to do what’s best for the people and the businesses that are included in it. Basically, everyone who operates inside of a market economy operates within a market. This is a framework that encourages activity and brings buyers and sellers together, depending on what they want and need. Most decisions are made by those people and businesses and are intertwined with supply and demand. The means of production and resources for operating a business are owned by private individuals and groups. For example, if a group of individuals wanted to launch a non-profit health care organization that offered free health care to everyone living in a certain city or area, there’s nothing to stop them from doing so. The only thing that would matter is that the health care organization would be able to compete to remain a viable going concern. If a group wanted to launch a very competitive software company that existed only for profits, it could. If a group wanted to launch a software company that shared all its profits with its employees and offer each employee free health insurance and lunch at lunchtime, it could. There’s nothing stopping any of these things from happening. The people involved and who intricately know and understand very local lifestyles and living situations make the decisions. This is not a top down command style structure that takes the decision making away from the people. This is actually a structure that encourages individuals to make their own decisions.

In reality, there are very few economies globally that exist under one distinct structure. Most are mixed market/command based and lean to either completely free market or a completely command style structure. The United States leans toward the market approach while Russia and China lean towards the command approach, but all are mixed. There are many elements of China’s economy that encourage free decision making and trade and there are many elements of the U.S. economy that are highly regulated or state run. Some examples of these areas in the U.S. might be social security and the military. Examples of market based approaches in China might be street vendors and restaurants. In both Russia and China, their respective economies moved somewhat away from the command style approach in recent years and have become more market based.

What Are the Most Economically Free Nations?

What does freedom mean as it pertains to economics? Well, ask yourself these questions: Am I in control of my finances? Can I buy what I want to buy? Am I free to make money? As much or as little money as I want? Can I generally do what I want? Can I employ myself anywhere I want (if hired)? If I decide to own a business, can I produce what I want? Can I hire and fire who I want? Are banks free to decide on lending terms and who gets funds and who doesn’t? If you answered yes to all of these questions, you live in a very free society, economically speaking. If you answered no, then you may live in quite an oppressive nation. In general, over the past decade or two, countries around the world have become more economically free. More and more people are able to make their own decisions. The spread of free market capitalism is a huge driver of these changes. Less free economies are generally built upon socialism and communism. So basically, if you wanted to open up a computer coding firm or a coffee shop in Boulder, Colorado, in a free society, you would have no problem doing so. In a command driven economy, such as one built upon communism, you might not be. In those types of economies, the government makes many of the economic decisions.

Every year, a report is put out by the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal. This report lists most of the countries around in the world in order of their level of economic freedom. This report is called the Index of Economic Freedom and it analyzes 50 different categories to determine scores for which countries rate. Another report that’s put out by the Frasier Institute does something similar. Ultimately, lists of nations are created that rank them from most to least economically free. It’s actually a very interesting list to look at because nations you would never think of rate very highly, while other nations rank very low. I’ll give you a hint for which country ranks very high, year after year: Hong Kong. And which ranks very low, year after year? That’s right, North Korea.

While most countries are listed, some aren’t. This is because they’re simply too volatile for the researchers to form any rational opinions on. Some of these countries include Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Somalia.

Let’s take a look at some comparisons between a few different years. First, I’ll list the twelve most economically free and the least economically free nations for 2015.

2015 Most Economically Free Countries

1. Hong Kong

2. Singapore

3. New Zealand

4. Australia

5. Switzerland

6. Canada

7. Chile

8. Estonia

9. Ireland

10. Mauritius

11. Denmark

12. United States

2015 Least Economically Free Countries

1. North Korea

2. Cuba

3. Venezuela

4. Zimbabwe

5. Eritrea

6. Equatorial Guinea

7. Turkmenistan

8. Iran

9. Republic of Congo

10. Argentina

11. Democratic Republic of Congo

12. Timor-Leste

Now let’s look at 2019.

2019 Most Economically Free Countries

1. Hong Kong

2. Singapore

3. New Zealand

4. Switzerland

5. Australia

6. Ireland

7. United Kingdom

8. Canada

9. United Arab Emirates

10. Taiwan

11. Iceland

12. United States

2019 Least Economically Free Countries

1. North Korea

2. Venezuela

3. Cuba

4. Eritrea

5. Republic of Congo

6. Zimbabwe

7. Equatorial Guinea

8. Bolivia

9. Timor-Leste

10. Algeria

11. Ecuador

12. Djibouti

And finally, we’ll look at 2020. Instead of twelve for this list, I’ll show seventeen. The reason for this is because the United States dropped a few positions and I wanted to include it in the list.

2020 Most Economically Free Countries

1. Singapore

2. Hong Kong

3. New Zealand

4. Australia

5. Switzerland

6. Ireland

7. United Kingdom

8. Denmark

9. Canada

10. Estonia

11. Taiwan

12. Georgia

13. Iceland

14. Netherlands

15. Chile

16. Lithuania

17. United States

2020 Least Economically Free Countries

1. North Korea

2. Venezuela

3. Cuba

4. Eritrea

5. Congo-Brazzaville

6. Bolivia

7. Zimbabwe

8. Sudan

9. Kiribati

10. Timor-Leste

11. Turkmenistan

12. Algeria

13. Sierra Leone

14. Equatorial Guinea

15. Burundi

16. Liberia

17. Iran

Take a look at how the countries shifted around. Also, who knew Estonia, Ireland, and Denmark were so economically free. Very interesting! Also, to find out what’s measured to come up with these rankings, check out the How Do You Measure Economic Freedom section on this Q&A page at the Heritage Foundation website.

To review live and up to date rankings for nations around the world, you can take a look at the Heritage Foundation website or you can look at Wikipedia.

How Do Regulations Fit into Economics?

Here are a few questions for you. What are regulations as they pertain to economies? Can there ever be a completely free market? Can there ever be a completely command oriented economy? What are regulations designed and used for? How do they help and hurt citizens and businesses? These are all great questions and once you know the answers to them, you’ll be well on your way to understanding regulations, their benefits, and their detriments.

Many economists describe regulations as the rules by which people, businesses, and economies must play by. We’ve all heard about regulations. Even when it comes to politics, the term “regulation” is thrown around like nothing else. Washington DC is full of lobbyists who try to either create to remove regulations, depending on who they’re lobbying for. Regulations can either make or break a business or industry. They can be a godsend or be the undoing of years of hard work.

Allow me to give you a quick and easy example. Let’s say that I would like to begin a skateboard selling company. I’ve done all the groundwork and incorporated my business. I’ve hired people, leased a building, bought all sorts of machinery, and invested tons of money into what I need to make this business happen. Sure, I’m flat broke at this point, but since my company will begin production tomorrow, I’ll soon be raking in the cash.

Now let’s say that just as soon as I fired up my machines to make the skateboards, one of my employees comes in to my office and tells me that the government just began a trade war with China, so we won’t be able to import any skateboard wheels like we wanted to. “Oh well,” I say. “Let’s make them ourselves.” “We can’t,” says the employee. “The government also just made a new regulation against using the raw materials we would need to make the wheels.” At this point, if I couldn’t find another place from which to import the wheels and if I couldn’t lobby congress to either change the regulation against using the raw material I need to offer me some special exemption, I’m out of luck. All that spending and preparation will have been for naught. Pretty bad, right?

Here’s another regulation for you and this type of situation is more common than you think. Let’s say I’m the CEO of a huge wealthy oil company. I’ve hired lobbyists to represent my company in Congress for decades. I’m best friends with senators and congressmen and we’ve gone on far too many golf outings together. A few days ago, I caught wind that a competitor would like to open a new oil field in Alaska. I quickly got on the phone and called a few of my buddies in the government. I asked them to create a new environmental regulation that would forbid my competitor from moving forward with his new oil field. Yes, that’s how business operates.

In general, government regulations are meant to level the playing field. They will always be there and they’ll always bend and twist markets in different ways. And no matter how anyone tries to portray a particular market, it will never be absolutely free. There’s no such thing as a free market. There can be levels of freedom, but if there were such a thing as being completely free, that market and those around it would be thrown into chaos. Just picture a factory pouring its toxic waste into a nearby river. Forever. It’s simply an unsustainable idea. In general though, market oriented economies have fewer regulations and command type economies have more.

So, what do some of our current and past regulations do? Well, they do a whole lot. Think about the banking and health care industries. These are two of the most highly regulated industries on earth. Partly because they’re so consumer focused, but also partly because they’re so wealthy and don’t like competition. As stated above, many regulations have been written to keep competition away. Otherwise, they are oftentimes intended to reduce or eliminate intellectual property theft, protect consumers from any number of things, help enforce contracts, prevent fraud, and aid in the collection of taxes (government revenue). In the most basic sense, every type of economy uses a market to operate, even the most top-down command economies of the world. If someone sells something that someone else buys, no matter how regulated the transaction is, a market is at play. It’s just that working within a market that has fewer regulations can sometimes be easier. We’ve all heard of those countries that require an individual to wade through 18 different bureaucratic agencies just to obtain a business license. Those are command economies at work. The thing is, while it may be quicker and easier to launch a business in a market with few regulations, it’s also easier for the competition to take you out in unscrupulous ways.

If an economy is too regulated, people begin finding other ways to do business and these ways oftentimes won’t have government approval. These types of activities usually occur in a black market or what’s referred to as an underground economy.

Economies change all the time. They ebb and they flow, depending on what’s called for at the moment. This is why legislators continuously work on adding and removing regulations and tweaking the ones that already exist. It’s sort of like a balancing act. Those who are in control of such things need to consider the relationship between the freedom a market experiences and its regulatory burden.

What is Globalization?

There’s this thing out there called globalization. We’ve all heard of it, but do you know what it is? It seems to be one of those things that we listen to the talking heads on the news discuss. It also seems that we need to take a stance on it. Are you for globalization or against it? It’s not only economical, but apparently political as well. With good reason, so it seems.

Globalization has gotten popular over the past few decades. During this time, the world has seen a marked uptick in cultural, political, and economic ties between nations, trade blocks, and groups. One of the most visual indications of this is the increased trade we see so often. Whether it be with physical and tangible items or digital products and services, there’s no denying that the world has become much smaller. Even hard assets such as land, real estate, and businesses have seen and increase in international trade. Global financial capital is flowing more freely than it ever has.

Have you ever asked yourself why this increase in global trade has occurred? If you think for a moment, you’ll likely answer that question yourself. If not, I’ll tell you. First and foremost, digital communication is more prolific and less expensive than it’s ever been in the history of the world. And with the creation and existence of the internet, more people, businesses, and organizations can now buy, sell, and communicate than ever before. The internet and access to digital communication has laid the groundwork for an explosion of trade. While all of this was happening though, shipping cargo by both air and sea has become less expensive as well. The reason for these lower transportation costs can be explained by looking at shipping competition as well as improved efficiency.

Beyond this, tapping into global intellectual assets has played a huge factor in global trade. Because of the proliferation of global communication, talented employees can be accessed like never before. Today, companies are looking to employees from all over to help create computer software, digital website applications, financial products, travel and vacation planning, different types of entertainment, such as music, books, and movies, architecture, various designs, and so much more. All of these things can be easily transmitted over the digital communication cables that lie deep beneath the sea. And the best part is, the cost of this type of communication is dropping every day, while the quality is rising.

Finally, international trade agreements and treaties between nations have spurred global trade activity. Although these agreements are topics for rabid political debate, there’s no denying that they’ve played a large part in what’s going on today.

For many nations, the ratio between exports and GDP has risen. Some nations have fared better than others in this department. There are reasons for this, and those reasons are varied. Sometimes a nation can offer something that’s desired internationally and sometimes there’s simply an abundance of what a nation can offer that they can’t use themselves. If you think about a random country, perhaps they have an abundance of copper in their ground, but don’t have a developed economy that calls for that resource. By opening up internationally, they can mine and sell that copper abroad and the income from that alone might drive their GDP higher than it’s ever been. Conversely, if a nation such as the United States, with its huge GDP and wide diversification, increased its imports and exports, their effect wouldn’t be as dramatic as a nation’s with a smaller economy. Larger economies contain much more of the division of labor internally and don’t call for many imports. Nevertheless, globalization is on the rise and the majority of nations around the world are all for it. It’s been highly profitable for many. In particular, as globalization grows, nations with lower incomes will change the most. They’ll see their trade increase dramatically, which will help their economies tremendously. This, in turn, will rise the quality of life for millions, if not billions.

Questions & Answers About Economic Systems

There are quite a few sections about economics in this post and I’d like to take this opportunity to give my take on a few textbook questions that get asked in regards to economic systems. If you aren’t sure what economic systems are, please read through this page in its entirety. You’ll gain some wonderful knowledge.

Here are the questions and my answers to them. Enjoy!

Answers to Questions About Economic Systems

1. The previous posts define private enterprise as a characteristic of market-oriented economies. What would public enterprise be? Hint: It is a characteristic of command economies.

There are actually many different examples of public enterprises, even in nearly total market economies. By definition, a public enterprise is one where the state owns all are part of the business. The state then controls the enterprise via a public authority. Examples of these types of enterprises are closer than you think. The roads you drive on are likely owned and managed by some form of government. Various types of utilities may be public owned. Telecommunications, transportation, fuel, just to name a few. Think subways, buses, bridges. They’re all publicly owned. A few more are the United States Post Office, various highway departments, the U.S. interstate highway system, and toll road authorities. The list goes on.

2. Why might Belgium, France, Italy, and Sweden have a higher export to GDP ratio than the United States?

For the more complete answer to this question, you’ll definitely want to see the bottom paragraph of the first section on this page. For the short answer, these nations may have higher export to GDP ratios than the United States because they’re markedly smaller economies. When a smaller economy has a resource they can offer the world, that they can’t fully use themselves (because there simply aren’t enough people), they can sell abroad. This will increase their exports. In the previous post, a copper mine was used as an example. In this post, France’s wine industry can be used as an example. If France can produce much more wine because of its robust wine industry than it can consume, that wine can be sold across borders, driving up the nation’s exports. The United States can easily absorb all the wine it produces internally. With 330,000 million people in the nation, all the wine that’s grown nationally can be sold nationally. Because of this, exports of wine may be low for the United States.

3. What are the three ways that societies can organize themselves economically?

The three ways societies can organize themselves economically are traditional, command, and market. For a full explanation of each, please see the above related section.

4. What is globalization? How do you think it might have affected the economy over the past decade?

Globalization is the buying, selling, and trading of goods and services internationally. Please see this post for a full description. This phenomenon most likely has grown the entire U.S. economy over the past decade, but not without it’s setbacks. Because the U.S. is a consumer based economy, it imports more than it exports. By importing lower priced goods, manufacturers have been put out of business in the United States. But, since prices have been lower, the consumer benefited. Consumer driven economies are ultimately hollowed out by cheap imports. Eventually, much of the manufacturing and production bases will disappear locally and the population won’t have the employment prospects it once had. Because of this, unemployment will grow and incomes will drop. Eventually, even robust economies such as the one in the United States won’t be able to support themselves and may fail, turning into third world nations like so many others. Then, once prices and demand fall due to depression, manufacturing will return and the economy will transform itself into an export one.

5. Why do you think that most modern countries’ economies are a mix of command and market types?

Mixed economies consist of both public and private sectors. There are good reasons to include both and those reasons revolve around public interest and profit. The private sector is allowed to profit, but is taxed higher when those in charge deem profit to become excessive. The public sector is generally non-profit and exists in the public interest. Government itself is non-profit. Roads and bridges are non-profit. The patent and trademark office in Washington DC is non-profit and so are many other governmental departments and institutions. Regarding the private sector, profits energize entrepreneurs and stimulate growth and innovation. Most of the modern innovations and much of what we rely on today as societies has been invented and created by entrepreneurs.

6. Can you think of ways that globalization has helped you economically? Can you think of ways that it has not?

Simple put, because of globalization, I am able to buy more with less. I can also tap into various markets around the globe to expand my personal purchases as well as business purchases. Goods and services I may not have access to locally, I can now purchase abroad. The downside of this is that, being a computer programmer, my own job may be outsourced to a less expensive alternative. India is known for inexpensive programming services. So no matter how cheap my import options may be, I may soon not have any money to buy them.

What Was the 2008 Financial Crisis?

I had a friend ask me this very question a few days ago. I guess he wasn’t paying attention when it happened. Either that, or he had no interest and anything that occurred didn’t affect him. I personally wasn’t very affected by anything that was going on at the time, so whatever the financial crisis was about wasn’t top of mind. Over the years though, I’ve read lots about it. What I’ve uncovered is startling. What’s even more startling is that what kicked off the financial crisis in the first place hasn’t even been resolved, so what will come next will be an utter nightmare. I won’t get into that here. I won’t even get into the nuts about bolts of what went on during the years that led up to 2008. What I will get into will be the general story of the mini-depression we went through as a nation and a world at the time. Bird’s eye view stuff.