I’ve been studying photography for quite a while now and I can’t tell you how many times I refer back to the basics to reassess my shooting style and capabilities. It seems that each time I do this, something new comes to mind that I can take advantage of. And the primary area of “basics” I look back to is exposure. When it comes to photography, there are few concepts more critical than this one. That’s why I decided to write a post that explores it in detail.

In this post, I’m going to discuss the three primary elements that make up, or affect, exposure. These three elements, in some circles, are called the “Exposure Triangle.” They are aperture, shutter speed and ISO.

What Is Exposure?

Most simply put, exposure, when relating to photography, is the amount of light that makes it through the various camera apparatus to the image sensor. If an amount of light that’s let through is too great for your photo’s intent, your photo will be “whitish” or washed out (overexposed). If the amount of light that’s let through is too little for your photo’s intent, your photo will be dim and dark (underexposed).

When folks discuss camera exposure, they often enjoy using examples to help explain what things are about. So far in my journey, I’ve heard two that makes sense to me. I’ll go over both of them here. The examples have to do with the human eye and a rain bucket.

The Human Eye

The function of the human eye (and most other eyes for that matter) can be quite easily compared to the function of how a camera works. Within and around the eye, there’s an iris, an eyelid and an overall sensitivity.

The iris of the eye is quite similar to a lens aperture, in that the both shrink and grow in relation to the amount of light that’s allowed to pass through to a sensor. The eyelid can be compared to the camera’s shutter. Both the eyelid and the shutter open and close with the intent to control the passage of light. And finally, both the eye and the camera have a sensitivity that is inherent to them. The eye uses a retina to adjust for this sensitivity and a camera uses ISO. Both move, or can move, and change based on available light and the photographic intent.

The Rain Bucket

The rain bucket example is a fun one because it’s really easy to understand. It’s a bit longer to explain than the eye example, but it’s worth it.

Let’s pretend it’s raining outside. The rain isn’t coming down too hard – just hard enough for a steady fall. When using the rain bucket example, we can compare the volume of rain that’s falling from the sky to the ISO setting we utilize on our camera. Sometimes there is all the rain in the world and sometimes there’s not much rain at all. Again, in this case, we’ll say the amount of rain falling is medium.

Let’s also say that we’ve got a bucket that we can place outside to catch some rain. The opening at the top of the bucket can be compared to the aperture of a camera lens. If the bucket has a big opening, a large amount of rain is let through, therefore filling the bucket faster. If the aperture on a camera is large, a lot of light is let through.

If we only wanted to catch a certain amount of rain water, it would be silly for us to leave the bucket out in the rain all day. Depending on how much rain we wanted, we would limit the length of time we leave the bucket outside. This can be compared to the shutter speed in a camera. Just as if we quickly place the bucket outside that then pull it back in really fast, we can set the camera to quickly open its shutter and then close it just as quickly, limiting the amount of light that’s allowed to pass.

I’m going to give a scenario to better illustrate what I’m talking about. Say we wanted to catch one gallon of rain water. If the rain is still falling at a medium rate (ISO), we have two settings we can adjust to meet out goal. We can either use a bucket with a narrower opening (aperture) and leave it out in the rain for a longer period of time (shutter speed) or we can use a bucket with a really wide opening (aperture) and leave it outside for a shorter amount of time (shutter speed). If the rain begins falling harder, we can adjust both of the variables to compensate for the heavier downfall.

As you can see, the three settings work together and offer a variety of flexibility. Since, oftentimes, environmental variables are out of our control, we set our cameras to make the best use of what we’re facing.

In this post, I’m going to cover some specifics on how aperture, shutter speed and ISO affect camera exposure. In later posts, I’m going to discuss the related characteristics of each of these areas and how they can increase a photographer’s creative license.

Shutter Speed

If we use another example to explain shutter speed, we can do it like this: close your eyes. Now open them very quickly and close them again. At first, all you saw was darkness. For that split second, you saw light and then when you closed them again, you saw darkness. You probably remember what you saw when you opened your eyes. Consider that a photo.

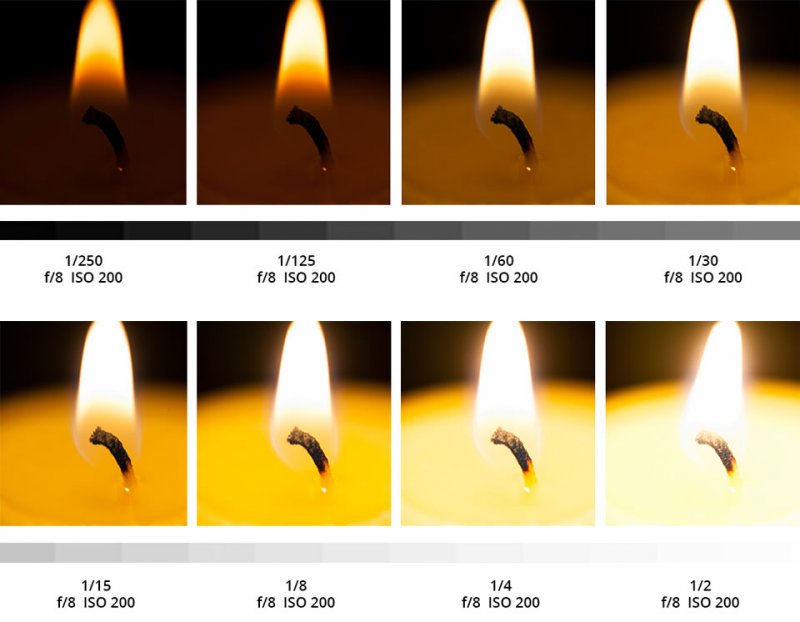

In a camera, a shutter is the mechanism that covers the sensor. When it opens, it allows the sensor to “see” light. Shutter speed is the measurement that’s used to determine how long the sensors sees that light. The longer the shutter is open, the more light will pass through to the sensor. The more light, the brighter the image.

Shutter speed is measured in seconds and since most photos are taken in normal daylight, the speed will generally be less than a second, or a fraction of one.

Below, I’ve created a handy list of when you might use a specific shutter speed. Please take a look at it to get an idea of how fast a shutter might move under a particular circumstance. All measurements are in seconds.

1/4000 – 1/1000: Use this speed when you are photographing extremely fast action that’s very close up.

1/500 – 1/250: You may want to use this speed for every day action shots, such as sports or wildlife. Also, you can use this speed for hand held photography as well as when using telephoto lenses.

1/100 – 1/50: This is an every day speed that works well when hand holding your camera without a zoom lens.

1/30 to 1/2: Use this speed to add motion blur to your photos.

1/2 – 2: You can use this speed to take still shots with movement in one portion of it, such as with rivers and waterfalls, for a “silk” effect. You’ll need a tripod for this type of photography.

1 – 30+ seconds: You must use a tripod for this speed. It’s primarily used for night and low light photography.

Aperture

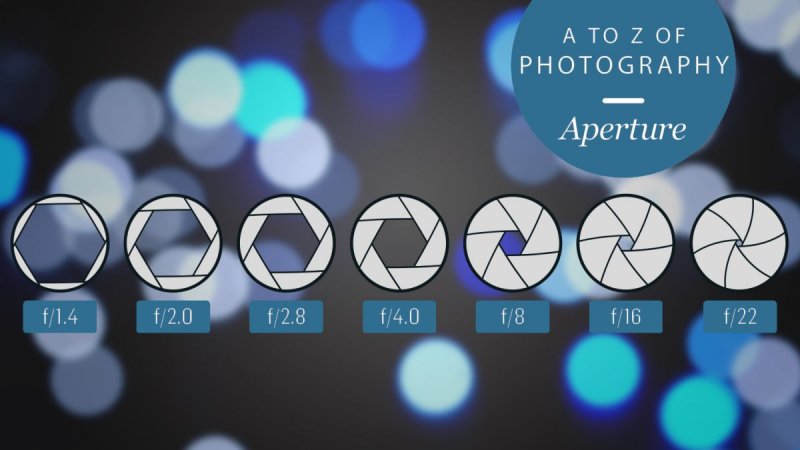

As part of your camera lens, the aperture acts just like the iris of your eye. The difference is, the aperture is constructed of metal blades that are controlled by either you or your camera’s automatic settings. The aperture opens and closes, much like a flower’s petals do during the day and during the night.

Aperture directly controls how much light passes through the lens into the camera. It’s the size of the hole that does this – the larger the hole, the more light. The smaller the hole, the less light.

Sort of like shutter speed fractional values, aperture size is specified in terms of f-stop values. This is where people get confused. The smaller the f-stop value number, the larger the aperture and the larger the f-stop value number, the smaller the aperture. Now, notice how I said “f-stop value number” and not just “f-stop value.” That’s because f-stop is a ratio. It’s written like this:

f/22

This refers to the ratio of the size of the aperture to the focal length of the lens.

I’ve been told that a good way to remember this ratio is that a larger number stops more light, resulting in a smaller hole. A smaller number stops less light, resulting in a larger hole.

Photographers like to use a lot of lingo. For instance, when a photographer says they are “opening up the lens,” they are actually increasing the size of the aperture (lower number). Similarly, they may say they are “stopping down,” which means the same thing.

When looking at actual f-stops, you can view full stops, half stops or third stops. I’ll give you some examples of what full stops look like:

f/1.4

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

f/11

f/16

f/22

ISO

ISO determines how sensitive the camera’s sensor will be to the incoming light that both the shutter speed and aperture control. Years ago, photographers specified their ISO values by the film they placed in their cameras. Now, since film is rarely used in the general population, a photographer can control their ISO value simply by turning a dial on their camera.

I’ll talk more about ISO values in later posts, but I want to mention that, in general, it’s more desirable to utilize a lower ISO value. As the ISO value increases, digital noise increases in the resulting photo. Unless there’s a reason for it, keep the ISO value as low as possible on your camera. The good news is, camera manufacturers have come a long way in reducing much of this noise, so photographers will soon have the luxury of utilizing much higher ISO values, with clean results, than ever before.

Before I finish this section, I wanted to tell you that common ISO values include 100, 200, 400 and 800, with higher and lower values populating both sides of this spectrum. Those higher and lower values are generally for specialty photography though.

Camera Exposure & Metering Modes

Every time you half press your camera’s shutter button, the camera “meters” your scene. Metering is when the camera’s light sensor assesses the given light that’s in front of it. Sometimes, it’s very easy to measure the light because there’s not much contrast in the area, but sometimes the camera has difficulty because there are bright spots as well as dark areas where you’d like to take your photograph. Because the camera is only able to capture an average of the light in any given zone, its exposure result may not fit your needs. Your resulting images may be either over exposed or under exposed. Luckily, there are additional tools contained within a camera that can assist you with acquiring the perfect exposure. I’ll explain all this much more clearly below.

Let’s work through a quick example to clarify what I just attempted to explain above. By the time you’re finished reading the paragraph, you’ll likely understand how difficult a camera’s job at getting the right exposure truly is. Let’s say that you point your camera straight at a wall that’s painted half black and half white. One side is super dark and the other is super light. If you were to meter the scene, what type of exposure would your camera choose to return you? If the camera says, “Hey, the black part of the wall is really dark. I better increase the exposure to compensate for that,” you’re going to end up with a photograph that’s way too bright on the white side. Sure, the black side will look good, but the white side will be useless. If the camera chooses to reduce the exposure because it determines that the white side is so bright, the resulting photo will be great on the white side, but ultra dark on the black side. So what’s a camera to do? And on top of that, how is the camera supposed to know what you’d like it to do? It’s almost a no-win situation for the camera.

Average Reflectivity

There’s this thing in the photography world that’s called average reflectivity. When a scene’s lighting, all combined, is 18% grey, it’s said to be of average reflectivity. Light bounces off the surfaces of objects in any given scene and a camera’s light meter absorbs that light. If you were to point your camera at a wall that’s emitting 18% grey, your camera would have no problems metering the scene correctly. But when you point your camera at the corner of a room that’s got a desk and a lamp in it, how is the camera to know whether it should brighten the really dark area under the desk or tone down and darken the brightness of the light bulb inside the lamp? It can’t have it both ways, but as I said above, there are things we can do to help the camera out.

And just to go back to the example I gave directly above, if the camera chose to brighten the dark area under the desk, the lamp light would cause an overexposed image. If the camera chose to darken the light coming from the lamp, the dark area under the desk would cause an underexposed image. I’m sure you’ve seen a picture of someone who’s standing in front of the sun. The camera meters the scene in such a way as to darken the sun somewhat, but inadvertently blacks out the person completely. They end up looking like a silhouette. This is the same kind of thing that happens when the camera tries to darken the scene because of the light coming from the lamp. It completely blacks out the darker area under the desk.

Metering Modes

There are a few different settings that we can take advantage of to steal some control back from the camera. By default, the camera will, as I said above, average all the light in the scene, but by changing a setting or two, we can isolate where in the scene the camera looks for light. This is super helpful in very diverse areas. The settings I’m referring to here are called metering modes and there are commonly three of them.

Evaluative/Matrix Metering: With this setting, the camera divides the entire scene up into a grid that’s got equally size partitions. Each of the partitions is equally weighted and all of them are averaged for one common exposure. This is the setting I was referring to above. It’s usually set by default.

Center-Weighted Metering: If you were to draw a circle at the center of your scene that covers about 60%-80% of the area and then weigh that circle heavily in regards to the light that’s in there, you’d have a center-weighted metering setup. The outer edges of the scene are used when metering as well, but they aren’t taken into consideration nearly as much as the center portion is.

Spot Metering: Similar to above, but this type of metering only covers 1%-5% of the center of the scene. This is like a laser focus on a very specific area’s light that you’d like to take into account. While the spot is generally locked to the center of the scene, some cameras do offer the ability to lock the spot metering location to a focus point. That’s very handy because you can move it around.

Exposure Compensation

As good as the above setting options are, they sometimes just can’t handle a scene that’s got lots of bright and dark areas. Sometimes, it’s better to take full control and tell the camera exactly what you’d like the exposure to be. In times like these, it’s best to use your camera’s exposure compensation feature. Basically, this feature allows you to brighten or darken your exposure by what’s referred to as stops. I used this feature all the time and it’s super helpful.

What is the Exposure Triangle?

In this next section, I offer a different perspective on what I shared regarding exposure up above. If you have any questions about any of this, please be sure to ask in the comment section below.

Out of all photography topics out there, this one is my favorite. I love teaching others about the theory behind what we do and if I can help someone understand this simple concept, I think they’ll run with it. The ideas behind the exposure triangle, while seemingly daunting early on, are actually rather simple. Once a budding photographer is able to grasp how light reaches a camera’s sensor, the faster they’ll excel at the hobby or profession.

There are three parts to the exposure triangle. They are aperture, shutter, and ISO. Each affects either how much light is able to reach the camera’s sensor or how the sensor reacts to the light that reaches it. Two of these parts are physical, meaning they’re mechanical aspects of the camera or lens, and one part is electronic, meaning it doesn’t contain any moving parts; it’s controlled by circuitry.

Each of the three parts of the exposure triangle are simple to explain and are rather straightforward concepts. The aperture is contained in the lens. It acts like the iris acts in an eye. It shrinks and grows, depending on how small or large either the camera or the photographer wants. The smaller it is, the less light that passes through the lens into the camera. The larger, the more light that passes through. It’s that simple.

The camera’s shutter is situated directly in front of the sensor inside of the camera itself. It’s a plastic or metal shade that moves away and exposes the sensor when the time is right. The length of time the shutter moves out of the way is called shutter speed. The longer the shutter is out of the way of the sensor, the more light that’s able to touch the sensor. The less the shutter is out of the way, the less light that’s able to pass.

The ISO controls how sensitive the camera’s sensor is to light. It acts sort of like a stereo amplifier acts. As you turn up the volume on an amp, the sound gets louder. As you turn the volume down, the sound gets quieter. As you turn up ISO values, the more sensitive to light the sensor becomes. As you turn the values down, the less sensitive the sensor becomes.

The main crux behind learning photography is learning how these three parts of the camera work together. For every change you make in one part of the triangle, another is affected. Everything is a negotiation in photography. These negotiations can be frustrating, yet rewarding and fun.

Aperture sizes are represented in f-stops. If you’ve been learning about photography for any length of time, you surely have heard of these. Basically, each f-stop you hear of is just another size of the aperture hole. Lenses vary in the number and sizes of f-stops they offer, but some sizes are standard. Take a look at the graphic below to get an idea of what aperture sizes look like.

Thank you TechRadar.

In a typical lineup, each f-stop is either a doubling or a halving of light that passes through the lens. If you start at a large aperture size and go to a small size, you’ll be halving each step of the way. These sizes are f/2, f/4, f/5.6, f/8. f/11. and f/16. Larger hole sizes are represented by lower f-stop numbers, such as f/1.2 and smaller hole sizes are represented by higher numbers, such as f/22.

Shutter speeds work similarly to aperture sizes. For each “stop” in a shutter speed, there is either a halving or doubling of light that’s allowed to pass through to the sensor. Typical shutter speeds range from 30 seconds to 1/4000th of a second. Take a look at the following graphic to see how slower and faster shutter speeds can affect the exposure of an image.

Thank you B&H.

A camera’s ISO is set in stops as well. The ranges of ISO values are varied from camera to camera, but they usually start at a low number (and sensitivity) like 100 and climb all the way up to 16,000 (high sensitivity) and higher. Again, each stop is either a halving or doubling of sensitivity (exposure), so an ISO 100 is half as sensitive as ISO 200 is.

These are the basics of the exposure triangle as it pertains to photography. There’s much more to each of these areas, but for now, this is plenty to chew on if you’re new at this. Going forward, we’ll discuss how each change in any one of these aspects can alter the outcome of a photo. I’ll talk about the goods and bads of altering aperture, shutter speed, and ISO.

The Best Way to Get Perfect Exposure

What’s the best way to obtain the optimal exposure for your photographs? That’s easy. You’ll need to practice and experiment. And you’ll also need to make a lot of mistakes. Those mistakes are critical to your experimentation. After all, what will you have to compare if you don’t take some lousy shots as well as some good ones? It’s not like anyone ever runs out of film anymore, so enjoy the process and shoot away.

In this section, I’d like to discuss a few ideas that may help you out during your exposure experimentation. More specifically, I’ll talk about how you can use your camera’s exposure compensation feature to create a mood with your photos and inject some overall creativity into your shots. I’ll then discuss your camera’s spot metering feature and how it can teach you a lot in regards to exposing a scene. And finally, I’ll talk about bracketing your shots. By bracketing, you’ll essentially cover the gamut of possibilities when it comes to exposure. You’ll underexpose and overexpose – on purpose. The benefits of doing something like this are plenty. I’ll get to all that below.

For each of the scenarios I discuss below, the camera I describe will be set to Program mode. The reason for this is because in that mode, there’s flexibility. One area of such flexibility is exposure compensation.

Creatively Using Exposure Compensation

Mind you, anything that I describe in this section can also be accomplished inside of Adobe Photoshop. It’s easy enough to lessen or add to the exposure of a photo. But, as I always say, it’s better to accomplish as much as possible with the camera first before heading into post-processing. If that’s done, the ultimate quality will be greater.

To add some creative exposure to a photograph, you’ll first want to set your camera up on a tripod. Then, meter your scene the way you normally would, allowing the camera to do all the work. Take and review your shot. This will be your baseline. Next, with your camera’s exposure compensation feature, reduce your exposure by one stop. Take another shot. After that, increase it by one stop from the baseline. Take a shot and compare the three images. As you’ll notice, the mood changes with each one. If you want, you can under or over expose even further, just to see what happens. The goal of this exercise is to allow you to see how exposure affects scenes and images. If you get used to this extremely handy feature, you’ll have the ability to use it on the fly in the future. You’ll also know when it can be useful.

Spot Metering

Depending on the model of camera you have, you may or may not have the spot metering exposure option available to you. If you don’t, look for something called “partial metering.” If you’ve got that, use it. Next, head outside and find a scene that’s varied with bright spots as well as shadows. Spot metering allows you to dial in a very specific exposure depending on an area of your scene. It’ll brighten or darken your shots depending on how the area you dial into is illuminated.

Find an area within your scene that’s fairly neutral and of neutral lighting. Anything can be neutral, from the bark of a tree to the siding of a house. Expose your shot based on that neutral area and take the photo. Again, this will be your baseline. Next, find an area that’s brighter than the other areas. Do the same thing – expose your shot from that area and take the picture. Finally, find a darker shadowed area and follow the same steps. Upon review, you’ll find that your results are similar to those of the first exercise. The difference is, in the first exercise, you manually made the exposure changes and in the second, the camera did it for you, based on the relative brightness or darkness of the areas in your scene.

Bracketed Exposure

This is the most fun of the three, by far. This is an automatic way that your camera does the same exact thing as you did manually in the first step. On many DSLR and mirrorless cameras, there’s a feature that allows you to take three, five, seven, or more shots in succession to one another. For each shot, a different exposure compensation setting will be chosen. So for each time you push your shutter button, three or more photos will be captured by the camera. If you’re using a tripod or if you can hold your hands very still, the photos should be identical, expect for the exposure. What’s the use of this, if not merely experimenting? Well, you can think of it as an insurance policy. Let’s say the camera’s standard exposure that’s been chosen is a bit off. By capturing a range of exposures, your photos won’t be a total loss. Also, by capturing a range of exposures, you’ll be able to easily merge all of your photographs to create an HDR (high dynamic range) image in Adobe Camera Raw. There’s a lot that you can do with multiple images, so begin thinking about the possibilities. Just remember, when engaging in this type of exercise, a tripod always comes in handy.

Here are a few tips for you: when finished experimenting or using your camera’s exposure compensation feature, be sure to set it back to zero. You wouldn’t want to quickly grab your camera for that money shot and have your settings out of whack. Also, when capturing bracketed images in the first scenario above, you’ll need to press your shutter button each time you want to take your photo. In the last scenario though, you’ll only need to press the shutter button once. The camera will take all of the photos in succession. You’ll hear the shutter go click, click, click very quickly.

Do you have any other ideas in regards to photography exposure? Do you have any questions? If so, please add to the conversation down below.

Leave a Reply