The most popular aspect of shooting in aperture priority mode on your DSLR camera is the ability to control your photo’s depth of field. For those of you who aren’t versed in photographer lingo, depth of field is the plane of focus in a scene. In other words, in any given photograph, it’s possible to have particular sections of it that are in focus as well as those that are out of focus. You may have seen this type of photography prevalent in macro shots. Portrait photographers are also notorious for taking advantage of a shallower depth of field, causing the subject to remain clear and isolated, while the background is blurred out. Conversely, landscape photographers prefer a deeper depth of field, which keeps the entire photo in focus.

I’ve previously discussed shutter speed and how it affects exposure. Aperture size also affects exposure – just in a different way. And as you become more versed in the sport of photography, you’ll begin to learn how the two can play off one another.

In this post, I’m going to discuss aperture – what it is, how to use it while taking photos and what affects it can have on your photography as far as lighting and depth of field are concerned.

Measuring Aperture

It’s common knowledge that aperture is one of the more confusing areas of learning basic photography. It doesn’t have to be though. If you simply section out the elements of what aperture is, how to measure it and its effects on depth of field, it should become straightforward.

First, I’ll discuss what aperture is. This one’s easy.

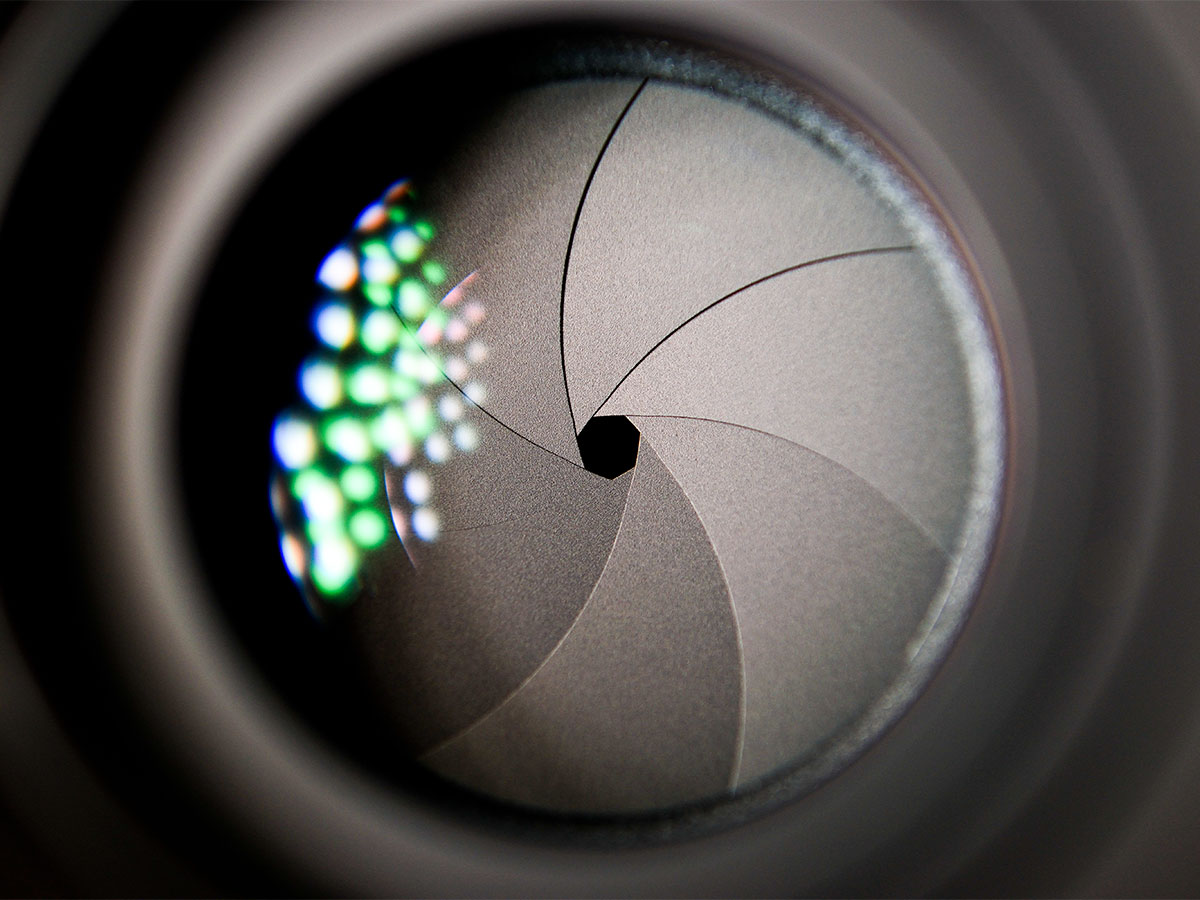

Basically, aperture is the size of the hole in the camera’s lens that lets light through. The hole is created by sliding metal fins that move against each other as the photographer chooses and sets the desired aperture size. It’s helpful to compare a lens’s aperture to the iris of an eye – the mechanism that shrinks and contracts, depending on how much light is needed. More mechanically, you can compare aperture to a flower in a garden. During the day, the flower petals open up and during the night, they close. Think of the metal fins inside the lens as the flower petals.

Next, I’ll cover how to measure aperture.

Aperture is measured using an “f-stop” scale. Each “stop” is denoted by a number. It looks like this: f/number. Just switch out the word “number” with an actual number. If you take a look below, you’ll see the f-stop scale in all its glory.

f/1.4

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

f/11

f/16

f/22

There are a few interesting areas to note regarding the above scale. The first area that requires understanding is that the smaller the number, the larger the actual aperture opening in the lens. The larger the number, the smaller the opening. We’ll keep things simple by considering each f-stop as a fraction. So if we think of a fraction, we know that 1/2 is larger than 1/1000. If you keep this in mind, it’ll be much easier to think straight while you’re in the field.

The next area that requires understanding is that in the above scale, each “stop” is a halving or doubling of light that hits the camera’s sensor. So, while the numbers aren’t exactly halves or doubles of each other, the size of the aperture is. Just as shutter speed uses stops as a measurement, so does aperture.

If you’re looking at your digital camera right now and seeing a larger quantity of aperture sizes, don’t worry. Many cameras today display selections as third-stops, meaning there are stops in between those in the traditional aperture scale.

Finally, I’m going to talk about what effect aperture size has on depth of field. Later on in this post, I’ll go much deeper into the definition of depth of field, but for right now, we’ll keep things easy.

If you were holding a camera in your hand right now and dialing the aperture size down to the lowest available setting, you’d be increasing the size of the aperture. By “opening up” the aperture, you’d be narrowing the depth of field. All this means is that the plane of focus is getting thinner. So, if your aperture is large enough and you were taking a photo of someone’s face, the front part of their face may be in focus and the back of their head, perhaps their hair, might show some blur.

Conversely, if you dialed the aperture size up to the highest setting, you’d be decreasing the size of the aperture. By “closing” the aperture, you’d be deepening the depth of field. In this case, the plane of focus is getting much wider. This type of aperture size is great for landscape shots, where the entire area is the subject and everything needs to be in focus.

Using Aperture Priority

One benefit of using shutter priority is that you have control over how much light hits the camera’s sensor. Another benefit – a more creative one – is that you can control the motion blur, or clarity that’s in your photos.

Aperture priority is similar to shutter priority in that you have control over certain aspects of your photos as well. Like shutter priority, you can dial in exactly how much light hits the sensor. But unlike shutter priority, with aperture priority, you can adjust depth of field, or focal blur that’s in your photos. And that’s what I’ll be talking about in this section.

As I mentioned above, depth of field is a range of focus. It measures how much of the image is in focus, from front to back. I’m going to give you a few examples to help make this concept a bit more clear.

Let’s say you are taking a photo of three people. They are all standing in front of you in a staggered fashion. The first person is about 5 feet away, the second person is about 10 feet away and the third person is about 15 feet away.

The first photo you take of these people will be taken with an aperture setting of f/2.8, which will give you an extremely shallow, or narrow, depth of field. Now, just to let you know, depth of field is measured from the point of focus. So if you’re focusing on the person in the middle (the one who’s 10 feet away), only that person will be in focus. The front person and the rear person will both be blurry. If you decide to focus on either one of those other folks, the remaining two will be blurry. This is because the depth of field with an aperture setting of 2.8 is only a few feet.

As a reminder – if you focus on the first person in our lineup, as I mentioned before, they will be in focus. The person behind them will be blurry and the person behind them will be really blurry. Depth of field has a range that increases with distance.

Let’s change things up a bit. Let’s say that you want to remove some of the blur from the front person and the rear person when you focus on the center person. To do this, you can dial down the aperture size (so the aperture hole is smaller) to something like f/11. By doing this, you’ll be widening, or deepening, the depth of field, which will clear up some of the blur from the two people I referred to earlier. Now, these folks will still be blurry in the same fashion as they were in the first example, but it won’t be as dramatic. I’ve personally taken photos like this and the risk I’ve run into is that the photo looks like it was taken in error. While the center subject was perfectly clear, the remaining two subjects weren’t exactly in focus or out of focus. It looked like I didn’t know how to set the camera properly because there wasn’t much definition. Just a word of caution.

Lastly, let’s say that you wanted to take a picture where everyone was in focus. You can do this by truly deepening the depth of field as much as your lens will let you. If you set the aperture to something like f/22, when you take the photo, all three people will be in focus. That’s because the depth of field will be so great, or deep, your camera and lens will capture everything.

As you can see, by toying with aperture settings, and as a result, the depth of field, we can add creativity to our photos and truly guide the viewer’s eye.

What is Lens Speed?

For years, as I was learning about photography, I would hear about something called “lens speed.” I never really looked into its meaning, which I think hurt me because while reading all those Amazon.com reviews on lenses I thought I was interested in, I didn’t really have an idea of what the reviewers were referring to when they described the speed of the lens in question. As time passed, I decided to look into the meaning of what I’m talking about here and I thought I’d share it with you.

Lens speed refers to the size of the available aperture of a particular lens. As you may already know, all lenses aren’t created equally. Some have set apertures, some have apertures that only move within a narrow range and some have apertures that move within a wide range. Some lenses offer aperture sizes that hang out near the low side with large openings and some offer just the opposite with small openings. With all these variations, it’s sort of challenging to “talk photography” with people without some sort of a rule. I’ll give that rule to you right now:

Fast Lens Speed – These are lenses that offer low aperture f-numbers and wide apertures. These lenses let more light through and are referred to as “fast” lenses.

Slow Lens Speed – These are lenses that offer high aperture f-numbers and narrow apertures. These lenses restrict the light that passes through and are referred to as “slow” lenses.

Now, there’s a whole lot to discuss when it comes to lenses and all their respective attributes. Much too much to go over in this post. Keep an eye out though, because I’ll be writing about lenses in future posts.

Small Aperture For Landscape Photography

Many amateur photographers like to head outside in search of the ultimate landscape shot. They set their camera to “auto,” find what they want to capture and snap away. While many of their pictures will be winners, they might be winners by luck.

What I mean is this – when shooting in auto mode, a photographer doesn’t have much say when it comes to following some of the guiding principles of photography. Oftentimes, cameras set their internals up to offer the best exposure. They don’t necessarily set things up with the photographer’s intent or creativity in mind. Because of this, a photographer, amateur or otherwise, needs to take back control from their camera.

If you recall what I wrote above, you know that if you want a very deep depth of field, you should use a smaller aperture size. Shooting landscape would be a prime example of this type of setting. In general, “land” in a landscape is the subject, so you’d want as much as possible to be in focus, from front to back. Unfortunately, even with a very high aperture number, you won’t be able to grab everything and have it in focus.

What to do? Well, the first thing you should do is find out the furthest you can push your aperture size. What I mean is, even if your lens’s aperture can close almost all the way down, you might not want to do that. If you do, and the conditions are not optimal for that setting, the quality of your photographs may suffer. Folks in the business call this the lens’s “sweet spot.” It’s where you can set your lens to give you the best output. Now, you have to understand, while taking landscape photographs, the sweet spot most likely won’t lie at f/22. It’s likely going to be somewhere much more moderate. So with that in mind, you’ll need to compensate with other guiding principles.

When taking landscape photos, the primary aspect you need to concern yourself with is what you want to focus on. As I mentioned directly above and in other prior sections, you won’t be able to have everything in focus, meaning, your depth of field will be finite. In order to deal with this, you’ll need to determine how deep your depth of field is and what your primary subject is going to be. Even in landscape, you’ll surely need to prioritize something.

As a general rule, when taking landscape photos, you want to focus on what’s one third of the entire landscape away. I know, that’s a bit to digest. Let me say this another way – say your camera is sitting on a tripod that’s pointing towards a mountain. Your tripod is at mile number zero. You are the beginning of the scene. Now let’s say that the horizon of the mountain is nine miles away. So, we can say that the subject of the photograph is nine miles deep.

In order for us to take a nice looking photo with a decent variety of clarity and focus blur, we should focus on the three mile mark. That will allow our camera’s depth of field to give us clarity in the foreground of the photo and slowly blur, probably beginning at the six mile mark or something like that, all the way back.

Here’s the issue though. What if we focus on the three mile mark, but that’s not where we want to point the camera? What if that excludes some of the scene? That’s easy to fix. When you auto-focus on something with your DSLR camera, you can push the shutter button down half way, in order to allow the camera to focus and meter. If you don’t let up and keep the shutter button half way pushed down, you can move the camera anywhere you want. When you have the scene you desire in the viewfinder, go ahead and continue to push the button down all the way to take the picture. This should give you your desired results.

Because it’s difficult to see exactly what you’ve got in focus while in the field, it helps to take advantage of a technique called bracketing. Bracketing, and in this case, depth of field bracketing, means that you take several shots, each using a slightly different setting. If we were taking a picture of a landscape and wanted to focus on something in particular, but weren’t sure if we were getting the shot we want, we could continually adjust the focus, from the foreground to the background, in hopes that one or two of them are what we’re after. Photography isn’t an exact science and since digital film is free, we should use it extensively.

Zooming In For Close-up Photography

One of my favorite types of photography is macro. I love to get really close to a subject, take a few pictures and then review them inside on my computer. It wasn’t long after I began taking these types of photos that I realized something odd was happening when I’d position my camera, take a picture, re-position the camera, take another photo and so forth. For each shot, the depth of field would change dramatically – even when I hadn’t changed the aperture setting.

It’s common knowledge, and I’ve talked about this above, that the wider the aperture in a lens, the shallower the depth of field. What’s not so common knowledge is that depth of field can also change based on the camera’s proximity to the subject. Well, actually, the depth of field can seem like it’s changing based on the camera’s proximity to the subject.

If you take a picture of someone who is standing in a field in front of a forest using an f/8 aperture, you’ll get a photo with the subject that’s clear and a background that’s soft. Now, if you physically move your camera back about ten or twenty feet and zoom in on the person, so they fill the frame as they did earlier, while keeping the same f/8 aperture, the subject will remain clear, but the background will appear softer than it did in the previous shot.

You’re probably asking, “How can this be?” What’s going on is an interesting phenomenon. While the background isn’t really any softer, it appears larger, or close, and therefore appears softer.

To make this easier to understand, think about taking a photograph with a wide angle lens. If you’ve ever done this, you know that you can essentially be on top of something, take a picture of it, and it’ll appear as though that something is ten feet away. That’s the fun part of using a wide angle lens. You can use it for some really neat tricks. Now, if you use a zoom lens or a magnifying filter at the end of a lens, exactly the opposite will happen. Things will appear very close to you.

While I’m not going to get into the deep specifics of what’s going on behind the scenes in this post, I will tell you that with various lenses, objects in the photographs will appear as though they are either closer or further away from one another, with no apparent changes in settings between lenses. It simply depends on the relationship of the lens glass between each other.

DOF Preview

One of the most critical areas of taking photographs in the field is awareness. You need to be aware of, not only what’s going on around you, but also what’s going on inside your camera. And just because you set your aperture to a particular size, doesn’t mean that you’re going to get what you expect. There are various factors that can affect depth of field in a photo, as I just mentioned above, and those factors need to be addressed as to minimize surprises during photo editing.

The tool of choice to test aperture is called the depth of field preview button. Usually, it’s a small, unmarked button on the left side of the camera (if you’re looking through the viewfinder) and it resides right next to the lens. What the button does, when pressed, is offer the photographer a simulated representation of what the photograph will look like when taken. To see the simulated representation, you’ll need to look through the viewfinder.

When taking photos, your camera always keeps the aperture at its widest setting to allow as much light through as possible. It does this to aid the photographer while they are trying to set up a shot. It’s not only until the photographer meters the camera by pushing the shutter button down half way that the camera actually sets the correct aperture for the picture. So when looking through the viewfinder when the camera isn’t metered, it’s impossible for someone to grasp what the depth of field output will look like.

By pushing the depth of field preview button, the camera acts as if you push the shutter button down half way. It sets the aperture to give you a view of things to come.

How Wide Can You Go?

I absolutely love pushing my lens to the limit when it comes to shooting shallow depth of field. It creates a lot of drama for my macro shots and really isolates my subjects when taking shots that are further away. I have run into issues when opening up my aperture too much though and I’ll share a few of those issues here.

First, when I open up my lens as far as it’ll go, things get really tough to photograph. Oftentimes, when I shoot macro, the depth of field is so narrow that what’s clear for one inch will blur a half inch closer or further away. If I don’t have the camera stabilized, I’m almost certain to take a blurry photo throughout. But, this type of shallow depth of field makes for great photos, so fool around with it a bit to see what you can do.

Next, by opening up a lens all the way, you become susceptible to the altering of background images. While both backgrounds will most likely be blurry while shooting at f/2/8 and f/4, both backgrounds might not display the shapes of what appears in them identically. Some shapes may be higher or wider than they would be at a different aperture, so this is something to keep in mind as well.

To learn more about photography, be sure to visit my photography category. Thanks!

Leave a Reply